JAZZIZ Magazine Editor’s Letter

JAZZIZ Magazine Editor’s Letter

“Jazz is known all over the world as an American musical art form and that’s it. No America, no jazz,” said drummer and bandleader Art Blakey. “I’ve seen people try to connect it to other countries, for instance to Africa, but it doesn’t have a damn thing to do with Africa.”

Blakey knew a thing or two about the music and educated several generations of musicians in his rolling graduate school the Jazz Messengers. He was, of course, right.

In the beginning, there was America.

From its origins in the mud of a complex, troubled, cultural mix to its essential tension between the needs of the music, the individual, and the group as a whole, jazz is a fundamental expression of the Great American Experiment. But jazz is no longer America’s exclusive domain. In fact, the most important development in jazz at the turn of the century is its globalization.

It’s been a long time coming. For starters, the economic, technological, and military success of the United States after World War II made it a cultural superpower. As a result, by the turn of the century, cultural goods created or claimed by the United States — be it rock ’n’ roll, basketball, jazz, or film — had become part of global culture. And so, over the past 50 years, Elvis Presley shook up Mexico City, James Brown put West Africa to dance, and Hollywood became everybody’s storyteller.

In jazz, musicians such as Kenny Clarke, Bud Powell, Ben Webster, and Dexter Gordon found such an avid, respectful audience in post-World War II Europe that they moved there. In fact, around the world, people of disparate heritages embraced American culture and, in many instances, set out to recreate it in their own image.

As once happened with cars from Japan or electronics from Korea, developments such as Rock en Español, European jazz, and Latin American basketball were initially laughed off as inferior imitations of good ol´ American products. But now, Japanese cars are widely prized, Colombian rocker Juanes is a star, and Argentina is the reigning Olympic basketball champion.

In jazz there has always been a place for non-American players — a Django Reinhardt, an Abdullah Ibrahim, or a Gato Barbieri — but they have been the exceptions, and their contributions, by and large, considered little more than side trips or exotica. But what began as a one-way monologue and evolved into a hesitant, tentative dialogue has become, especially over the past 20 years, a many-sided conversation.

Non-American musicians still study and revere the great masters, but no longer aspire to imitate them. They are fluent in American jazz but have found the blues in their own cultures. They have their own notions of swing, standards, and improvisation. And they’ve found partners in serious, committed, adventurous jazz producers and record label owners such as Giovanni Bonnandrini, Manfred Eicher, Kurt Renker, François Zalacain, Siegfried Loch, Jean Jacques Pussiau, Fernando Trueba, and Leo Feigin — the kind of people, it’s worth noting, that corporate America couldn’t push out the door fast enough.

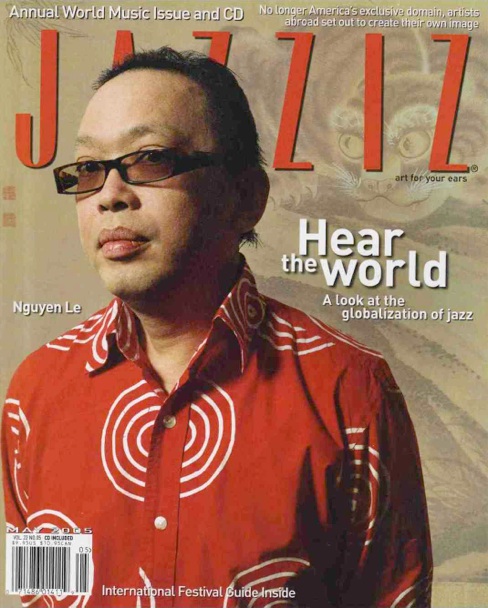

In this issue, we explore the globalization of jazz through some leading artists working here and abroad. They represent only the proverbial tip of the iceberg.

Blakey’s “American musical art form” still mirrors the country that produced it, but if you listen closely you’ll hear the world.

This piece appeared in JAZZIZ Magazine, May, 2005