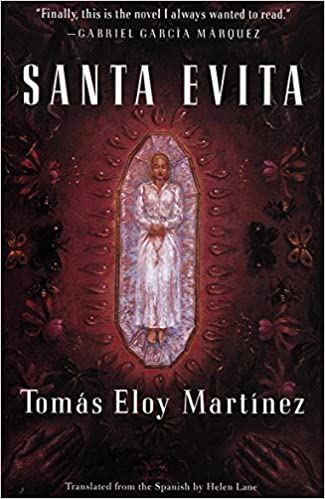

Santa Evita a novel by Tomás Eloy Martínez. Translated from the Spanish by Helen Lane. (Alfred A. Knopf)

Santa Evita a novel by Tomás Eloy Martínez. Translated from the Spanish by Helen Lane. (Alfred A. Knopf)

Eva Perón has long been a character in search of a novel.

A modestly talented actress of humble origins, María Eva Duarte worked, hustled and intrigued her way up in the Argentine society of the 1930s and ’40s, became the companion and wife of Juan Domingo Perón as he rose from military man to strongman and president of Argentina, reinvented herself as Eva Perón, powerful political figure and died in July 1952, at age 33, as Evita, a popular icon.

Even while she was alive, the facts of her life were a work in progress.

She understood how politically potent a mix of fantasy and reality could be and used it remorselessly, with a sure hand and precise timing. From birth certificates and hair color to accounts of her role in Peronist politics, anything and everything was subject to change. Death settled nothing.

Hoping to minimize its powers as a symbol, the military that overthrew Perón in 1955 stole away her embalmed body and buried it in a secret place, where it laid for sixteen years before it was returned to her widower. Instead of diminishing, and benefiting from the fantasies of her disparate suitors, from guerrillas to pop music composers, Evita, and her myth grew even larger.

In Santa Evita, the fascinating novel by Tom’as Eloy Martínez about Evita’s peripatetic corpse and the characters and machinations determining its fate, Evita also overpowers the author, upstaging him while remaining elusive. But it’s an extraordinary defeat as the struggle leads Martínez into one of the richest, most insightful, and provocative novels yet on Argentina.

A true diva, Evita holds centerstage in Santa Evita imperiously, demanding attention by her mere presence. Her scenes crackle with tension and possibility. Even in Helen Lane’s pedestrian translation, Evita can go from high mindedness to pettiness or tenderness to violence – and back – in one second flat.

But Evita is not only her but also what others believe her to be. So in trying to grasp and hold her, Martínez lays a trap of facts and fantasy, moves forward and backward in time, looks for glimpses of her in the tales of others – her hairdresser, her embalmer, the Colonel in charge of disposing of her body, Martínez himself, writing a novel about Evita – looking at themselves in her reflection.

As he does, what comes into focus is Argentina, a country shocked by Evita and her beloved grasitas (greasers) out its delusions of being “Cartesian and European;” a country young and rich, confused about its identity, in denial of its brown skin and irrational impulses, full of arrogance about its future, yet holding a fascination with death bordering on necrophilia.

“Every time a corpse enters the picture in this country, history goes mad,” fumes someone as he considers the potential impact of Eva Perón’s embalmed body in Argentine politics.

Santa Evita is an epic struggle with memory and history, fought image to image,fact to fact, fairy tale to fairy tale.

Martínez battles the allure and beauty of Evita’s embalmed body with perfect replicas. He answers to her out-of-a-soap-opera life scripts by explicitly taking a plot out of a story by Jorge Luis Borges. He fights off her Cinderella by playing Tom Thumb, leaving crumbs of facts and observations along the way, hoping for a way back to clarity, reality, truth. “Perhaps history was not made of realities but of dreams,” a character wonders. “People dreamed of facts and then writing invented the past.”

The author himself ponders “If history – as appears to be the case – is just another literary genre, why take away from it the imagination, the foolishness, the indiscretion, the exaggeration and the defeat that are the raw material without which literature is inconceivable?”

Yet as astute and elegant a writer as he is, Martínez is at a disadvantage here. This is history as vaudeville act – and few have played such angle better than Evita.

After she hides from view – in Santa Evita she never quite exits, she just sort of fades like a vapor drawing – her presence can be felt like a fragrance or a curse. And even then, she remains large. It’s the novel that gets smaller or, more precisely, dull and sluggish. Like others before him, Martinez can’t let go. In the latter third of the book, a certain melancholy sets in. Scenes go on past their usefulness, minor characters overstay their welcome, things slow down to a crawl.

But it’s all for naught. By then, she’s beyond reach.

And yet, as it falters, Santa Evita is more illuminating about Eva Perón than most conventional biographies could ever hope to be with the small triumphs of proven facts. More important, in reaching for Eva Perón, Martínez might have found Argentina.

These are paradoxes Evita would certainly appreciate.