Astor Piazzolla imagined la hora cero as the time after midnight, “ an hour of absolute end and absolute beginning.”

Astor Piazzolla imagined la hora cero as the time after midnight, “ an hour of absolute end and absolute beginning.”

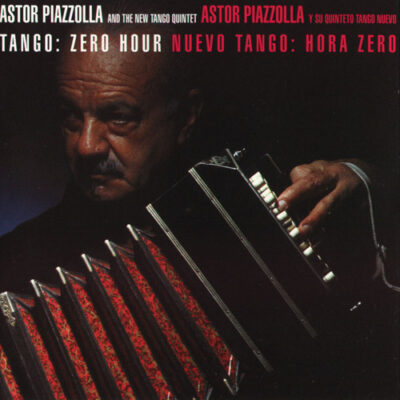

It was not by chance, then, that early in his career, he titled one of his breakthrough pieces “Buenos Aires Hora Cero.” It could not be by chance that, as he was entering his autumn days, he called the album that summed up decades of hard work and carried deep personal hopes and professional expectations, Tango Zero Hour. By the mid-1980s, Astor Piazzolla had long been celebrated in Europe, and finally, grudgingly, been given the respect he deserved in his native Argentina. The irony was that despite his American upbringing, recognition in the United States still eluded him.

In 1924, when Piazzolla was three, his family moved to New York from Mar del Plata, a seaside resort south of Buenos Aires. They stayed in New York, with a brief interlude, until 1936. It held the memories of his childhood – streetfights, Cab Calloway heard from the sidewalk outside a Harlem night club and the Italian solfege teacher who taught him the secrets of making spaghetti sauce. While living in New York, his father gave him his first bandoneón, the button squeezebox that is the quintessential tango instrument. It was also in New York, where, more than twenty years later, as a grown man, a musician just trying to make a name for himself and feed his family, enduring what he once called “the hardest three years in my life,” that Piazzolla learned of his father’s death and composed his most famous work, the moving “Adios Nonino.”

Piazzolla rarely visited New York after leaving the city in 1960. When he returned briefly to record Zero Hour, twenty-six years later, he was musically at a peak.

He had distilled years of apprenticeship as a tanguista, the lessons learned from his classical teachers, his fascination with jazz, and the memories of a thousand bruising battles a one-man tango avant-garde into music that was sophisticated, profound and emotionally direct. He also had an extraordinary instrument with which to play it, for at Zero Hour, he was into a ten year run with The New Tango Quintet.

His Octet Buenos Aires, organized in 1955 after he returned to Buenos Aires from Paris, energized by his studies with Nadia Boulanger and his encounter with Gerry Mulligan´s Octet, marked the great divide between traditional tango and what came to be known as Nuevo Tango. Piazzolla´s first quintet, which remained loosely together from 1960 to 1970, pushed the boundaries of Nuevo Tango as quickly as it established them. The short-lived Conjunto 9 (1971-72) in fact a string quartet and a quintet featuring a trap drummer – sparked his most elaborate writing for large ensemble.

But The New Tango Quintet, convened in 1978, was in a class by itself.

Having come together through a mix of vision and chance, the quintet on this recording features Piazzolla on bandoneon, Fernando Suárez Paz on violin, Pablo Ziegler on piano, Horacio Malvicino Sr. on guitar and Héctor Console on bass. It was a fortunate mix. A jazz player at heart, Malvicino had once injected jazz-style improvisation into the music of the Octeto Buenos Aires – a revolution within a revolution in tango. With a background in both jazz and classical music, Ziegler was an ideal partner. “The difference in this group,” Malvicino recalled recently,” was that Astor for the first time had a pianist with a jazz background. Ziegler was not an authentic tanguero, but a guy who learned a lot with Astor and became a tanguero – whether he wanted or not.” The reserved Console, schooled on tango and classical music, was the foundation of the quintet, rock-solid but also nimble and exceptionally sensitive. The classically trained Suárez Paz, in what had traditionally been the starring role in Piazzolla´s group, proved to be a brilliant technician with a heart to match and grit to spare.

By the time The New Tango Quintet went into the studio, it had assumed the spirit of its leader – it was cosmopolitan and reo (streetwise), erudite but also passionate, elegant yet tough. In the span of one piece, the quintet could suggest a chamber group one moment a rugged, Saturday night neighborhood tango dance band the next. As Ziegler explains, “ By the time we recorded Zero Hour we knew each other by smell, and something had taken shape well beyond the scores. We all got along very well. We were very tight personally, we loved the music, and Astor loved the group. He loved his musicians. That’s what you hear. That and that stuff in the cracks of the music, the passion, the grime that came to the surface over years of playing together.” To this Malvicino adds, “It was clear this was not just another record. This was The Great American Adventure, the conquering of America.”

These nuances might have been lost on some producers, but in Kip Hanrahan, Piazzolla found someone who could not only hear them but appreciate and capture them. Initially, the Bronx-born Hanrahan might have seemed like a curious choice. He had an adventurous but small label, American Clave, and was best known as a composer of knotty Avant-ethnic fusion and a sui generis bandleader. (Coincidentally, the offices of American Clave were just blocks away from where Piazzolla had lived as a child)

According to Malvicino, “Astor was disenchanted with the big labels. He felt they had not treated him with respect. Kip loved Piazzolla. He had a tremendous admiration, a passion, for everything Piazzolla, and he knew his work from the days of his orquesta típica (traditional tango orchestra). Kip is not your average guy, he might not be easy sometimes, but he is great fun, has a great sense of humor, and he and Astor got along wonderfully.”

Throughout his career, Piazzolla wrote and arranged specifically for the musicians in his group. “Contrabajisimo,” the new work in the recording and perhaps the highlight of Zero Hour, is dedicated to Console. Piazzolla also constantly reworked his material, as if probing it from different angles. “Tanguedia III” opens with voices – the members of the group – reciting, mantra-like, the words tango, tragedia, comedia, kilombo (1) Piazzolla’s tongue-in-cheek formula for Nuevo Tango. Up close, you can hear Piazzolla himself kidding around in Italian, breaking up his players. The piece was first recorded in 1984, for the film he Exile of Gardel, but this version has a sinister elegance and greater weight. “Milonga Loca,” actually “Tanguedia II” and originally part of the same soundtrack, has become faster, looser, and crisper here.

“Concierto para Quinteto,” first recorded in 1971, not only features notable contributions by Suárez Paz and Piazzolla, it offers a glimpse of where Piazzolla was going with the group. “Ah yes, I had to take a test in rehearsals showing him that I was not playing jazz and I was getting a handle on improvising with the “Buenos Aires feel” that Ziegler had mastered,” says Malvicino. “ After Zero Hour I got carte blanche and improvised much more.”

These are demanding pieces, yet the individual playing remains consistently precise and intense throughout. As an ensemble, Piazzolla and his New Tango Quintet sound focused, loose, and forceful. They are in total control of the music and prove it by casually changing direction, moods, and dynamics on a dime.

Piazzolla immediately recognized that the quintet had accomplished something special, believing Zero Hour to be “…the greatest record I’ve made in my entire life. We gave our souls to it. This is the record I can give to my grandchildren and say “This is what we did with our lives.’”

After Zero Hour, the quintet would go on to produce one more masterpiece, the underrated La Camorra (Nonesuch/American Clave), a magnificent summation of tango history that stands as Piazzolla’s final tribute to those who came before him and a dare to those who might follow him.

With so much to choose from, Piazzolla fans will argue endlessly about favorite players, groups, arrangements, and performances. But sometime in May 1986, in New York, Astor Piazzolla, Fernando Suárez Paz, Pablo Ziegler, Horacio Malvicino Sr., Héctor Console, and Kip Hanrahan found their hora cero at exactly the same time.

Tango Zero Hour was released by American Clave in 1986 and reissued by Nonesuch in 1998. These notes appeared on the reissue.