Chucho Valdés. Photo by Alejandro Pérez

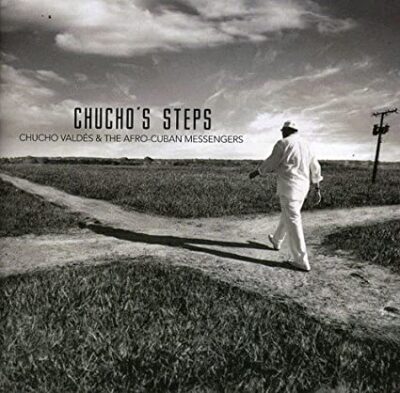

It’s tempting to hear Chucho’s Steps, the most recent album by Cuban pianist, composer, and bandleader Jesus “Chucho” Valdés, like a memoir of sorts.

After all, Valdés turned 69 on October and the image on the cover, not to read too much into it, shows him approaching a crossroads.

His group, his working quartet augmented here with a sax, a trumpet, and percussion, evokes the sound and brings back some of the material, of Irakere, the extraordinary Grammy-winning Afro-Cuban jazz-rock group Valdés founded in 1972. The music brims with energy and virtuosity as it elaborates on some of Valdés’ familiar musical interests. Some references are explicit, like naming his group The Afro-Cuban Messengers, or using titles such as “Zawinul´s Mambo;” “Julián,” named after his three-year-old son; or “New Orleans (A Tribute to the Marsalis Family).” Others are more oblique, like “Begin to be Good,” “Both Sides,” “Yansa,” or the title track.

It all suggests an artist looking back and taking stock.

“No, there was no plan, nothing premeditated about it. Those pieces came out spontaneously. It’s the kind of thing that happens as one creates,” says Valdés speaking from his home in Havana. “You write, work on the pieces, and as you do, they suggest other ideas. And I feel that’s the best way, because spontaneity is part of this music.”

Still, be it by chance or by design, Chucho’s Steps tells a story.

* * *

Jesús Dionisio “Chucho” Valdés was born in Quivicán, a town south of Havana, Cuba. He is the son of pianist and bandleader Ramon “Bebo” Valdés, a central figure in the golden age of Cuban music in the 1940s and ’50s, and a crucial musical influence for Chucho.

As the story goes, Chucho was a prodigy who was playing by ear at the age of 3. In fact, there is an anecdote, cited by author Nat Chediak on his Diccionario de Jazz Latino (Dictionary of Latin Jazz), of Bebo tricking his friend, the late Israel “Cachao” Lopez, about checking out, with his back to the player, “a young North American pianist.”

Chucho was then 4 years old.

By the time Chucho was 16, the elder Valdés was leading Sabor de Cuba, one of the epochal big bands in Cuba, and brought him into the orchestra, an extraordinary on-the-job training for a young, budding musician.

“He taught me everything about Cuban music, South American music, jazz, and how to work with an orchestra,” reminisces Chucho. “ He gave me the piano chair, and stayed as director, so I could learn how to work under a conductor. We did our shows and a million other things with that orchestra, including accompanying shows at the Havana Hilton. I learned a lot there. And with [Bebo] I learned to orchestrate because he is a master at that, “ he pauses, then continues. “He was my teacher. He still is.”

Some of those early family scenes are evoked in “Begin to be Good.”

“That piece has to do with the famous “Begin the Beguine,” ” says Chucho. “The rhythm is beguine, but it’s “Begin to be Good” because we used to listen “Lady Be Good” all the time.”

“That was the music we heard at home. On the radio, we had the privilege to hear the Glenn Miller band, Art Tatum, who was my dad’s idol along with Bud Powell and Monk. My dad was un bebocero del carajo (a hell of a bebopper),” he says breaking into a laugh. “And at Tropicana [the legendary Havana club where Bebo Valdés worked as a pianist and musical advisor] I heard people like Milt Jackson, Sarah Vaughan, Nat King Cole, and Buddy Rich. And that was not on the radio. That was right there, in front of me. In fact, I heard Nat playing so much piano that I liked him better as a pianist than as a singer. And then there were the jam sessions my dad took me to when I was 8 or 9, when he would play with guys like Stan Getz and Zoot Sims. For the American musicians, Havana was just a skip and jump from Miami.”

The family story, and Chucho’s world, in particular, was shattered when Bebo, in the aftermath of the Cuban Revolution, left for Mexico in October 1960. “Things got very bad,” explained Bebo some years ago. “People could not go to Tropicana because of the bombs, cars were set on fire. They even put a bomb inside Tropicana and a woman lost an arm.”

Bebo Valdés, 92, has not returned to Cuba since. Chucho was 19 and, nearly overnight, had not only had lost his father and beloved music teacher but had also become the head of his family.

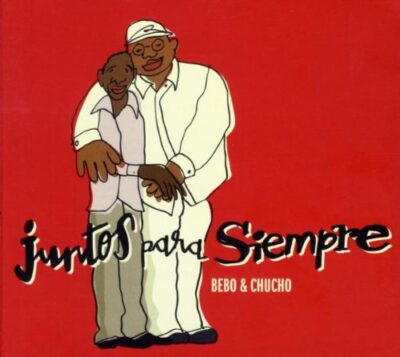

Chediak, who was also the producer of, among others, Juntos Para Siempre, the duet album by Bebo and Chucho Valdés, says how “Chucho has told me how the whole family went to say goodbye to Bebo at the airport — all except him. It was just too much anguish for him. Chucho grew up by his father’s side.”

Father and son didn’t see each other for many years.

Bebo eventually re-married, settled in Sweden, and started a new life. After he stopped touring, in 1972, he lived in genteel obscurity, playing hotel lounges until he semi-retired. In the meantime, Chucho’s Irakere exploded in the jazz scene. In 1978, the group appeared at Carnegie Hall in New York City. The senior Valdés went to the concert and, backstage, Chucho and Bebo reunited. They hadn’t seen each other for 18 years.

“There was never a big fight, some angry argument between them,” says Chediak. “What there was there was a great distance — and a great silence.”

Chucho says that the reunion with Bebo “was everything at once: It was easy, it was hard, beautiful, emotional, and musically, I think it was tremendous for both of us.”

After that encounter, they met again whenever Chucho was in Europe and, in 1994, through the efforts of friend-of-the-family, saxophonist and former Irakere member Paquito D’Rivera, Bebo Valdés got back into a studio and recorded Bebo Rides Again, which, improbably, re-launched Bebo’s career. (He has since recorded several albums and won 3 Grammys and 6 Latin Grammys)

Chucho was going to play on Bebo Rides Again but had to cancel at the last minute. He still sounds apologetic as he explains the circumstances.

Bebo and Chucho coincided later at a D’Rivera show in San Francisco and played two pieces captured on D’Rivera’s hard-to-find 1996 Cuba Jazz (90 Miles to Cuba). But the father and son reunion became fully realized musically in 2000 for Calle 54, the Latin jazz film by Spanish director and record producer Fernando Trueba.

“Just as in the shooting of any movie you have the story of the lead actor falling in love with the leading lady, in the shooting of Calle 54, theirs was the great love story, ” recalls Chediak, who was instrumental in the project and wrote the book about the shoot. “And after that, they became two drops of water coming together. There was no way of separating them. And for all his recordings and compositions, for Bebo, his greatest creation is Chucho.”

The reunion of Bebo and Chucho Valdés culminated in 2007 on Juntos Para Siempre, a duet recording that earned them a Grammy and a Latin Grammy.

“That’s one of the recordings I love the most,” says Chucho.

Chediak was with Chucho the night of the Grammys, after winning for Juntos Para Siempre, and recalls how “he and I were walking after the ceremony, just the two of us, our wives were elsewhere, and he kept saying to himself ‘ This is one of the most marvelous nights in my life. This is one of the most marvelous nights in my life.’ He had already won I don’t know how many Grammys by then, but this one was special, this one was with the old man.”

Chediak was with Chucho the night of the Grammys, after winning for Juntos Para Siempre, and recalls how “he and I were walking after the ceremony, just the two of us, our wives were elsewhere, and he kept saying to himself ‘ This is one of the most marvelous nights in my life. This is one of the most marvelous nights in my life.’ He had already won I don’t know how many Grammys by then, but this one was special, this one was with the old man.”

Bebo’s influence can not only be heard on Chucho’s playing and writing but his interest in the African roots of Afro-Cuban culture. Among his many achievements, in the 1950s, Bebo created a rhythm, the batanga, which in its use of the batá (a double head drum used in religious Afro-Cuban ceremonies) in popular music foreshadowed Chucho´s work decades later.

Irakere’s groundbreaking use of Afro-Cuban music in a jazz-rock context had an improbable inspiration — a chance encounter in Bulgaria.

“Paquito and I were in Bulgaria in 1968 and saw a Bulgarian group called Opus 65, led by an extraordinary pianist, Milcho Leviev, who later came to play with Don Ellis. Milcho used Bulgarian folk music which is in odd meters and we looked at each other and said ‘ We can do that with Afro-Cuban music.’ We have very rich African rhythms and a great variety of drums and percussion. Of course, we didn’t discover that. People like Mario Bauzá, Machito, and Chano Pozo had already done that, but we wanted to take it in another direction, with the batá. That was after Opus 65.”

The irrepressible D’Rivera laughed out loud when reminded of the scene.

“That’s true!. I can’t remember how we got to that rehearsal, but we were fascinated by these guys who were playing jazz in this impossible time signatures of Bulgarian folk music and improvising with the same ease we could have played a danzón,” he says. “ It was wild. And yes, it was an inspiration for us, especially at a time Cuba was closed out to the world. But Chucho always had an extraordinary talent to do that [fusion] and more.”

Valdés first experimented with batá drums on Jazz Batá, a remarkable 1972 piano jazz trio recording in which they replace the standard drum kit. He and percussionist Oscar Valdés (no relation) reworked rhythms from Afro-Cuban ritual music for Irakere.

Enrique Plá, Irakere´s longtime drummer, recalled how “ the idea was to bring to popular music rhythms that had not been used in popular music, rhythms from [the ritual music of the] Yoruba, the Arará, the Abakuá. And at first, I tried to translate them to the drum kit and I remember Oscar telling me ‘ no, no you play American, we’ll do the other stuff.’”

In “Yansa,” titled after the Yoruba deity of the wind and storms, Chucho Valdés takes the assimilation of these rhythms to jazz a step further.

In “Yansa,” titled after the Yoruba deity of the wind and storms, Chucho Valdés takes the assimilation of these rhythms to jazz a step further.

“I have retaken that storyline but with a different approach,” says Valdés. “In Irakere we treated the Afro Cuban rhythms in the standard rhythms of the Yoruba and Afro Cuban traditions, mostly in 6/8 and 12/8, in which the clave (a five-beat pattern that anchors much of Afro-Cuban music) fits perfectly. But now, instead of using regular time signatures I’m using odd meters, be it in 5/ 4, 7 /8, or 11 / 4 , and then I started mathematically mixing those with regular meters. I’d say this is a deeper work than we used to do, but then again, many years have passed.”

“ Yansa” is in 9/8, 5/8, 6/8 and the clave with the batá goes crazy, constantly changing, and it was a lot of work, but it’s there.” (Also, “Yansa” has a descending horn arrangement that is a direct quote from Irakere’s classic “Homenaje a Beny Moré.” “True. Other stuff on the record was chance, but that’s absolutely intentional,” laughs Valdés)

But “Yansa” is not the only place where Valdés looks back at his old group.

The elaborate “Danzón,” was a song that Valdés wrote for Irakere “and could never record.”

“We tried to record it, but to be truthful, it never quite worked out, so I took it off the repertoire. Now it sounds like I would have liked it to have sounded back then — and it’s the same tune.

Now we mix danzón, ballad, and cha cha cha and I love how it has ended up. But I had to wait 35 years.”

Valdés is an imposing man, tall and bulky, and moves with the grace, and deliberate pace, of a retired athlete. Yet at the piano, leading his Afro-Cuban Messengers at the recent Barranquijazz, the jazz festival in Barranquilla, Colombia, he seemed to leap up with an urgency and energy that belied his age. He has worked with his quartet — Lázaro Rivero Alarcón, el Fino, on bass; Yaroldi Abreu, percussion, and Juan Carlos Rojas, el Peje, drums – for years. For Chucho’s Steps, he added Reinaldo Melián on trumpet, Carlos Manuel Miyares on tenor sax, and Dreiser Durruthy on percussion, and vocals, and called the group the Afro-Cuban Messengers, a nod to Art Blakey and his bandstand university, The Jazz Messengers.

“Blakey was an influence for me from the beginning, “ says Valdés. “That was one of the groups I listened to the most: the Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers with Horace Silver. It was an influence later for the work in Irakere. Especially the use of riffs. In Cuban dance music, we had the mambos, which had interesting [chord] sequences but not very broad harmonically. In Irakere I started to change the mambos to riffs, and then the riffs became longer and more complex and, I think more interesting. That came from what Horace Silver wrote for Art Blakey, the riffs, and the harmony.

“The ideas for the brass came from a different place. That has to do with the work we did with the Orquesta Cubana de Música Moderna, which was a great big band. I tried to imitate that with four horns — two trumpets, an alto and a tenor sax — and with just that try to have the sound of a big band. Of course when you have monster players like Paquito D’Rivera, Arturo Sandoval, [trumpeter] Jorge Varona, and [saxophonist] Carlos Averhoff you can write anything you want and it will work.”

As for the small big band sound of Irakere, “the direct influence was Blood Sweat and Tears,” says D’Rivera.

“Cubans of our generation had a great love for the big band sound, but that’s an unmovable beast. At least you have to have 18 musicians. It’s a hassle. When we heard that Blood Sweat & Tears album with David Clayton Thomas, Lew Soloff, and Bobby Colomby that had three horns and sounded like a big band for us was like ‘Wow!’ The Blakey influence and the Afro-Cuban rhythms are something else, but the small big band sound of Irakere is directly related to Blood Sweat & Tears. Our teacher Armando Romeu [the director of the Orquesta Cubana de Música Moderna] transcribed ‘Spinning Wheel’ and other pieces and we played them with 5 saxophones, 4 trombones, and 4 trumpets.”

* * *

But directing and writing for an ensemble like Irakere also meant for Valdés’ piano playing to be subsumed in the overall sound of the group. Fellow pianist and bandleader Joe Zawinul understood his predicament and early on encouraged Valdés to pursue his own career, in parallel to Irakere. They became close friends and Valdés paid him tribute in Chucho’s Steps with “Zawinul’s Mambo.”

“That was a deep friendship. Very deep,” says Valdés. “He was one of my idols at the keyboards. He was a genius. And I got very good advice from Zawinul. I met him here, in Cuba, in 1979 at the Havana Jam [a three-day jazz festival featuring Cuban and American acts]. He came with Weather Report. He heard Irakere and was very complimentary of my playing and told me ‘ Listen that band is tremendous, but your piano playing gets lost in the orchestral sound. Don’t leave the band, but why don’t you put together a trio or a quartet on the side? ‘ And that stayed with me. And I saw him again sometime later in Martinique and he told me the same thing again – and that year I did my trio and my quartet, signed with Blue Note and started the series of solo piano and quartet [recordings].”

Valdés lightens up and bursts out laughing when told of a conversation with Zawinul, years ago, about boxing, obscure Latin American champions, and Zawinul’s surprising knowledge of boxing arcana.

“Oh yes. And I’m another big fan of boxing,” he says. “ And let me tell you: our conversations were more about boxing than music,” and he chuckles at the memory.

The elaborate “Zawinul’s Mambo,” which includes extensive quotes from “Birdland,” was in the works two years, highly unusual for this group, says Valdés. “Sometimes we take time to really mature things, and playing live sometimes gives you great ideas. From the initial version to the one we recorded we had a million changes,” says Valdés, who makes a point of noting that Zawinul got to hear it and approved of it.

The most striking composition on the record is the last: “Chucho’s Steps,” the title track, a virtuoso homage to John Coltrane’s “Giant Steps.” “Frankly, it didn’t start out like that,” says Valdés. “There is no harmonic reference per se to ‘Giant Steps.’ The connection is that ‘Giant Steps’ was a harmonically complex 12-bar piece and this is a harmonically complex 50-bar piece in which there are no repeats. I just started playing and things started to happen. I taped it, and when I listened to it, I thought that it was tremendous.

“The harmonies are all different but similar, so if you [make a] mistake you never come back to the path. It’s a harmonic exercise and it’s hard for me to play—and I wrote it.”

In many ways, it’s an ideal finale, and it touches upon a motif that recurs not only through the album but through Chucho Valdés’ entire’s creative life: that of a promise from one great musician to another. JT

This feature appeared in the February 2011 issue of JazzTimes