Picking cotton near Clarksdale, Mississippi, 1939. Photo by Marion Post Wolcott. Wikimedia

This is the heart of the Delta, a brooding, magnificent plain in northwest Mississippi that runs south to Vicksburg, east to Mississippi’s central mountain range, and spills over into Arkansas to the west and Tennessee to the north.

The blues were born around here at the turn of the century, and its ghosts still haunt the place. The markers are everywhere: gravestones standing in empty fields, a roofless, wooden shack at the side of the road, a weather-beaten barn, its paint peeling.

This was the music of poor, rural Southern blacks living under brutal conditions in post-emancipation times. It would seem it all happened too long ago to matter. The world is a different place now.

And yet.

The bewildering technology that surrounds us, the huge and increasingly remote corporations we work for, the communities we live in but are no longer part of, all have created what folklorist Alan Lomax calls “the sense of being a commodity rather than a person; the loss of love and of family and of place.”

And so, a music that speaks of loss and displacement, of rootlessness and the rage and despair of being at the mercy of large, sometimes incomprehensible forces still speaks to us today. It is a music of deceptive simplicity.

Deep emotions, metaphysical concerns, profound social observations are often distilled into a few verses, a quirky refrain, an unexpected hesitation, and presented as just a bit of Friday night good-time music.

It is a music with an unbreakable spirit.

We hear it, unadulterated, in the growl of John Lee Hooker, the last of the old master bluesmen. We hear it in the angry electric wail of Buddy Guy and the gentle observations of the great Mississippi John Hurt. We hear it, in all its elegance and power, in the scratchy recordings of Robert Johnson, Son House, and Charley Patton.

And we hear it in the playing of their descendants, white rock stars like Eric Clapton, who will be at the Miami Arena this week as he goes on the road to repay his debts to Muddy Waters, Willie Dixon, Howlin’ Wolf, and Elmore James. It is a music of elusive grace. It can be blunt as a hammer — until we reach to grasp it. Then it becomes evanescent as perfume.

And so, visitors come here to find answers and fill in the blanks. They come to gaze at people, stand-ins for those long gone or dead. They come to listen to the silence.

They pause before the acres of cotton, a still, deep green ocean dissected by a swath of brown-red soil that seems to stretch into the void. In the evening light, the tractor path suggests Moses’ parting of the seas.

But one man’s poetry is another man’s misery. And here, the other side of myth is often a drab reality shaped by need.

Johnnie Billington, 60, shrugs. With his graying hair and severe demeanor, dressed in a powder-blue suit and wearing a tie, even in the brutal midday sun, Mr. Johnnie, as he is called by people here, looks more like a school principal than a blues musician.

He is both, sort of.

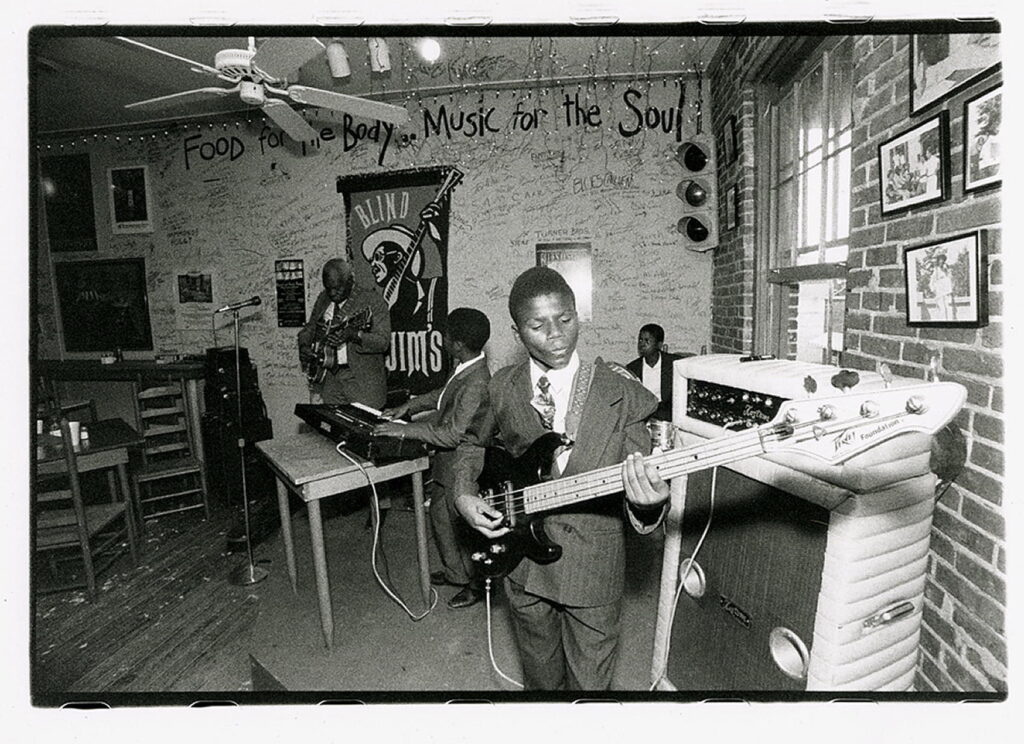

A mechanic by training and blues player by right, Mr. Johnnie, returned home from Chicago 18 years ago, “found no one was playing blues” and, without really planning to, became a one-man blues school. By now, a generation of Delta players has passed through his group. J.B. and the Midnighters currently feature a 14-year-old keyboardist, an 11-year-old bass player, and a 12-year-old drummer.

“Everybody has the blues some time,” Billington says with a rasp. “People just didn’t realize it. Now, the blues got popular all over the world because (people) listened to the singing and the lyrics and realized these people said it before. It might have been a hundred years ago, but it still applies today.”

Mr. Johnnie Billington (far back, left) and his young charges, the Midnighters, playing a gig in Oxford, Miss.

Songwriter W.C. Handy claims to have discovered the blues in 1903, when he heard a singer accompanying himself with a guitar while waiting for a train in Tutweiler, Miss. In truth, the origins of the blues are uncertain, though some of its sources — work songs, field hollers, Anglo-Scottish songs — are not. It was not overt protest music but rather, for the most part, about love and relationships. “The only deliverance most (blues) singers promise is sexual,” Francis Davis writes in The History of The Blues.

It is the manner in which issues were addressed, and the allusions in the texts, that often suggested larger themes. And while some students of the music dispute the claim of the Delta as the cradle of the blues — citing references to its presence in places like Texas, Georgia, California, and Missouri — over the years the Delta has nurtured several generations of blues musicians: from seminal, nearly mythical characters like Patton, whom Davis calls “the first Delta bluesman,” to modern-era performers like Waters, Hooker, and B.B. King.

Headstone of Charley Patton, “The voice of the Delta.” Photo by Jeffery Salter

Commercial recordings of the blues began to appear in the 1920s — Mamie Smith’s Crazy Blues is often cited as the first example — and flourished in “race records” marketed to black audiences. In the 1940s, folklorists John Work and Alan Lomax documented bluesmen such as Son House and Muddy Waters; those field recordings sparked an intellectual appreciation among a new, broader audience. Since then, the blues seem to be rediscovered periodically.

There was a revival in the late ’50s and early ’60s, an ideological as much as aesthetic re-evaluation related to the emergence of the folk-song-as-protest and the civil rights movement. This dovetailed into the late-’60s boom led by British rockers such as Clapton’s power trio, Cream; the Rolling Stones; John Mayall; the Yardbirds, and the original Fleetwood Mac.

The current revival was sparked in 1990 by the reissue of Robert Johnson’s recordings, an extraordinary critical and commercial success.

The blues endures because its power comes “from the struggle of the man against the destruction of his spirit,” says Lonnie Pitchford, 40, an up-and-coming country-blues guitarist best known for his versions of Johnson’s songs he learned from the bluesman’s stepson, Robert Jr. Lockwood.

“If I get your a– on the field right now, and I force you to work for me for free, how would you feel?” he says, biting the words, his anger almost palpable. “I just had an experience right here in Clarksdale this week. I was driving home, and the police stopped me and arrested me. For nothing. And when I asked why they put pepper gas in my face. Pepper gas.

“That’s the blues. It’s about expressing yourself about the feeling of being a man. And if you take that away from a man, you take everything.”

Clarksdale is a small town 70 miles south of Memphis. Here, memories of the blues are everywhere.

The red brick train station — once the counterpart of Chicago’s Union Station, the Ellis Island for poor Southern blacks migrating north — is a shell now. The waiting room is luminous and silent, its floor littered with broken glass.

Here is Issaquena Avenue, the heart of old Clarksdale. A few feet from the station is the “New World” district, where musicians played on sidewalk corners. A short walk in the other direction is Wade Walton’s Barber Shop and Lackey’s Entertainment, right behind the marker that denotes the site of Handy’s home.

A barber for most of his life, Walton counted Waters and Sonny Boy Williamson among his clients. But he was also a guitarist, singer and harmonica player who, in the late ’40s, played juke joints around town as a member of Ike Turner’s Kings of Rhythm. And here is Mrs. Z.L. Hill, 85, owner of the Riverside Hotel, now mostly a rooming house for laborers in the area. As she sits in the darkened hallway by the front door, Mrs. Hill — and in this town, she is always Mrs. Hill — might tell you, in the gentlest whisper, how, before she turned it into a hotel in 1944, the building housed the G.T. Thomas Afro-American Hospital and there, in that room past that door by the vending machine, is where Bessie Smith died in 1937 after a car accident on Highway 61.

Or she might recall some of her longtime residents, “very nice boys all,” for whom she “fixed supper no matter when they got back from the juke houses.” So she talks about Williamson and Hooker. Then, there was Robert Nighthawk, who left her a small cardboard suitcase with all his possessions, “nothing but records and a few things,” before going to the hospital from which he never came back. Or, if you ask her, she might tell you of raising Izear Luster Turner Jr., better known as Ike. “I knew him since he was a baby,” Hill says with a smile. “And when his mother passed on, he came to live with me. They used to rehearse downstairs in the basement. I used to make costumes for them.”

But the blues left the Delta years ago, or so the story goes, taken North in the great black migration of the 1940s. Some even point to that day in May 1943, when McKinley Morganfield, better known as Muddy Waters, a tractor driver from nearby Stovall Farms, took the train from Clarksdale to Chicago. Keyboardist John Ruskey, 31, curator of the Delta Blues Museum and director of its Blues Education Program, has heard the lament many times.

The remains of Muddy Waters’ cabin stand on the edge of Stovall Farms, where he worked as a tractor driver before heading to Chicago and fame as a blues musician. Photo by Jeffery Salter

“Ah, yes. Many people think the blues left the Delta with Muddy Waters,” he says, nodding with a faint smile. “But the fact is, there are a lot of musicians who stayed behind. This music is a part of life here. It never really died. It went underground to the juke joints and into the homes; it was played at weddings, birthdays, christenings. The only difference is that now it’s again played in the open.” Patty Johnson, 47, agrees. Johnson is a producer and partner at Rooster Blues Records, Clarksdale’s small but influential blues label, and founding member of the Sunflower River Blues Association, which stages the annual Sunflower River Blues and Gospel Festival here each August.

“We started finding youngsters who had gone into another form of music, say, funk or rap, but at home, they would play blues with their granddaddies,” she says. “They were just not comfortable bringing it out. . . .It did have a sort of bad image for a while. (And it) didn’t have the glitter or respect that rock ‘n’ roll or funk or even R&B had. “Also, for many, blues was about hard times, and they didn’t want to hear about it.”

Johnnie Billington remembers it somewhat differently. After moving around, from Clarksdale to Arizona to Chicago, he returned to the Delta in 1977.

“When I left, blues players were playing all over around here. When I came back, I (expected) to find what I had left, maybe get in a band and go play. It wasn’t just that nobody was playing in Clarksdale — no one was playing in the Delta. . . . I’d go to a club, and they’d have a deejay spinning records. Nothing live. I couldn’t believe it.”

Today, there are a few juke joints in Clarksdale — places like South End Disco, better known as Red’s, a no-frills, windowless room with a dozen tables, a pool table and electronic poker game and a space for the band next to the door; or the River Mount Lounge, with its raised deejay booth next to the dance floor, where the band sets up; and others, found along the back roads of the Delta and up in the hills.

Still, the blues here is the music of a community, not an industry. Like their forefathers, most blues musicians in Clarksdale today hold day jobs. They are carpenters, mechanics, laborers, construction workers who steal time from sleep to rehearse on weeknights, and play on weekends.

“When I was young, I started working as a sharecropper, and, oh, man, it was hard work,” says Wesley Jefferson, 52, a mechanic by day and a singer, bass player, and bandleader by night. “You have dreams, but everything was so hard. I was suffering, suffering. I guess that’s what pushed me to start playing. The blues is a tradition. It’s history. It’s my life. It’s where I come from.”

On this morning, he is bent over the engine of a white Ford. As if a reminder were needed, the door to the bay where he is working opens onto a cotton field. In the flat, wide-open Delta, distances are deceiving. And so, it seems, are notions of time and change. Here, the past is never far.

“Blues grew out of small communities. It was local music by local musicians,” Patty Johnson says. “Only a handful traveled. For everyone we’ve heard of, a Charley Patton, a Son House, a Robert Johnson, there probably were 10 who stayed at home. They might not have been that good, but then again, maybe some of them were. But they stuck around, lived their lives, didn’t get recorded and never got well known. That’s still true.”

At best, the alchemy of suffering into art is an equivocal craft, deceptively mundane.

It is also necessary. Sometimes we must be reminded that one man’s misery is another man’s poetry.

“No, the blues can’t ever die,” Mr. Johnnie says. “The music might not be exactly as you heard it a hundred years ago, but the lyrics is the blues and the feeling is the blues, and it will always be there. It’s the story of the people, and the only way the blues is gonna die is if all the people upon the earth die.”

This story first appeared on The Sunday Miami Herald, September 1995