By the time he was captured and killed in Bolivia, Ernesto “Che” Guevara was shadowed by failures. His last was leading a small leftist guerrilla group in the Bolivian mountains on a campaign to spark a continental war of liberation. Taken wounded after a battle with the Bolivian army on Oct. 8, 1967, Guevara was executed the next day on the dirt floor of a schoolhouse in La Higuera, a hamlet in southern Bolivia.

It was an inglorious end to an adventure that had become an unmitigated disaster.

His legacy has not fared much better: The Cuban revolution, of which he was one of the most prominent ideologues and leaders, has stagnated. Many leftist guerrilla movements did emerge in Latin America after his death, but they achieved few victories, and the region has turned to democratic elections and the free market, not revolutions.

Yet the Guevara mystique has endured — and now, in the ’90s, is flourishing.

For decades a potent political and cultural icon, Guevara has become the poster boy for revolutionaries and capitalists, evoking idealism and nostalgia, selling principles and a good time, ideology and better skiing.

This year, the 30th anniversary of his death, several new books and movies are out or due out that examine Guevara’s life and legacy. Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life (Grove Press), by American journalist Jon Lee Anderson, is in bookstores, and La Vida En Rojo (Life in Red) (Planeta), by Mexican political scientist Jorge G. Castañeda, will be published this week in Buenos Aires and later this year in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf. There are more to come.

Meanwhile, Ernesto “Che” Guevara: The Bolivian Diary, a Swiss documentary by Richard Dindo, premiered last September in New York. Several feature films are in the works in Argentina (one, El Che by Anibal Di Salvo, premieres next month) and a film directed by Michael Radford (Il Postino), described in the Warner Bros. press release as “an espionage thriller”, is scheduled to open in October. The film is based on the relationship between Haydee Tamara “Tania” Bunke, a German-Argentine intelligence agent, and Guevara. Bunke was killed in an army ambush in Guevara’s Bolivia campaign. The executive producer is Mick Jagger.

The Guevara mystique extends to contemporary plays and music. Rock-and-rollers born well after his death celebrate him in imagery and songs, from rap/metal band Rage Against the Machine to the Argentine group Los Fabulosos Cadillacs.

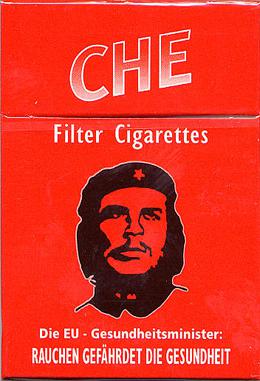

Meanwhile, Guevara has become a marketing tool. Recent years have seen a Che beer (in London; it was taken off the market after the Cuban government objected), a Revolution model of Swatch watches featuring his face and the Cuban flag (the Cuban government reportedly bought 10,000 from the Swiss manufacturer) and skis (last year the Austrian Fischer Ski and Tennis company, distributed out of New York, started a line, Revolution, promoted with Che’s image).

The Cuban government, after years of ambivalence caused in part by Guevara’s open criticism of the Soviet Union, resurrected him after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Nowadays — not a surprise given the realities of the post-Soviet Union world — cash-starved Cuba has turned Che into part of its tourist industry, selling everything from books and posters to T-shirts, ashtrays and key chains.

The Cuban government, after years of ambivalence caused in part by Guevara’s open criticism of the Soviet Union, resurrected him after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Nowadays — not a surprise given the realities of the post-Soviet Union world — cash-starved Cuba has turned Che into part of its tourist industry, selling everything from books and posters to T-shirts, ashtrays and key chains.

“Che is the last unplundered icon of the ’60s in popular culture, and now can be looted for commercial use in our entertainment culture,” says Anderson, author of Guerrillas (Random House, 1993).

Across geographical lines

A journalist who covered the political conflict in Central America during most of the ’80s, Anderson became interested in Guevara while researching Guerrillas. He noticed that fighters in places as disparate as El Salvador, Burma, Afghanistan, and Western Sahara spoke admiringly of Guevara.

“I started to wonder who was this guy who transcended time, geography, and such cultural differences,” he recalls.

When he looked for biographies he found either hagiographies or demonizations, Anderson said. He worked on his Guevara tome, a sober, well-researched biography, for five years, gaining unprecedented access to Guevara’s personal archives and diaries, Cuban and Soviet government files, interviews with Guevara’s friends and his widow Aleida March.

“There are people in the world who would like to see him still politically viable, and there are others who just like his commercial appeal,” Anderson says. “The companies nowadays don’t care if he was a communist; if they can make money off him, they’ll do it. Their attitude is: If Che sells, why not?”

For Castañeda, author of Utopia Unarmed: The Latin American Left After the Cold War (Alfred A. Knopf, 1993) and The Mexican Shock (The New Press, 1995), “the relevance of Che today is indirect.”

The central thesis of his book, Castañeda says, “is that Che becomes a myth worldwide and everlasting because his life intersects with a certain era.”

“He is not pertinent today because of his political ideas, not even because of his [revolutionary] example, as Cubans like to say,” Castañeda says. “He’s relevant as a symbol of the ’60s – and the ’60s do have great importance culturally in the world today. [The culture] we live today . . . we owe in large measure to the ’60s.”

A symbol for the masses

In the 1960s and ’70s, a time of great social change, Guevara came to embody the revolutionary ideal.

Then, he was seen by many as the committed and uncompromising anti-establishment figure who lived by his principles. It didn’t hurt his myth-making that he died relatively young at 39. And then there was the famous 1960 picture by Cuban photographer Alberto “Korda” Diaz, showing Guevara with his long hair and intense gaze. It crystallized the notion of the revolutionary as a rock star and religious icon all rolled into one, a rebel with a cause — James Dean with ideology.

Anderson, in fact, relates Guevara to American pop icons of the 1960s — Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix — and the death of a youthful, idealistic era.

“There is a desire to have a hero in these heroless times,” he says, explaining the fascination with Guevara today. “Who else is out there? Which leaders can you look up to? They all look like accountants.”

And the renewed interest in Guevara is also a reflection of “the lack of ideologies linked with taking power and transforming society,” Castañeda says. “There is a void. This is an era devoid of utopias.”

A question of ideals

Even as they despise Guevara for his role in the revolution, some Cuban exiles concede his stature as a global icon.

“I’m an adversary [of Guevara],” says Miguel Gonzalez Pando, director of the Cuban Living History Project at Florida International University. “I was in the Bay of Pigs; I was in jail. But I always take my hat off to an adversary that has lived according to his ideals, and that’s the case with Che.

“Although for most exiles Guevara represents all that’s wrong with the revolution, we cannot fail to acknowledge that within an international context, he became an icon of the poor, the downtrodden, those who were against any imperial designs.”

Miami-Dade Community College sociology professor Juan Clark, author of Cuba Mito y Realidad (Cuba Myth and Reality), points out that many exiles make a distinction between Fidel Castro and Guevara “because Castro is perceived more as an opportunist, while this individual was ready to die for his ideals.”

But, he adds, many perceive Guevara as “cold, unfeeling. They feel his work did enormous damage to the economy, and many remember his role as the chief at [the military fortress and prison] La Cabana, where so many executions took place.”

Becoming a legend

Born in Rosario, Argentina, on May 14, 1928, to an upper-middle-class family, Ernesto Guevara de la Serna was a physician by training. He became a political radical when his extensive travels through Argentina and Latin America exposed him to the disparities between rich and poor. Guevara met Castro in Mexico, joined his group, and by the time the rebel army took power in Cuba, he had become one of its top commanders.

For much of his time in Cuba, Guevara was second only to Castro, holding several positions in government, including heading the industrialization department at the National Institute for Agrarian Reform and president of Cuba’s National Bank. But by 1965, his plans for industrialization abandoned as a costly failure enmeshed in a power struggle with both Soviet and Cuban Communists, including Raul Castro, Fidel’s brother, and with the island firmly in the grip of the Soviet Union, Guevara stepped down from his posts and disappeared from public view. As it turned out, he had gone to Africa to join a guerrilla campaign in Belgian Congo, now Zaire. Within seven months, he had to be rescued.

Guevara secretly returned to Cuba. Still intent on starting a Latin American revolution, he set out on his ill-fated Bolivian campaign.

“In none of the different roles he played was he particularly successful, and in truth, he lost most of the battles he fought,” Castañeda says. “One of his traits is what the French call fuite en avant , escaping forward. Every time he was in a situation full of ambivalence, shadings, he solved it by jumping into the void. But he was a successful revolutionary.”

The real legacy of Guevara “is not his success or failure,” Anderson says. “But that he tried.”

Thirty years later, all that effort and integrity has made Guevara a cool ski pitchman, a dashing Hollywood leading man, a face in an ashtray. Banality might yet do to Che what his enemies could not.

This story appeared in the Miami Herald, April 1997.