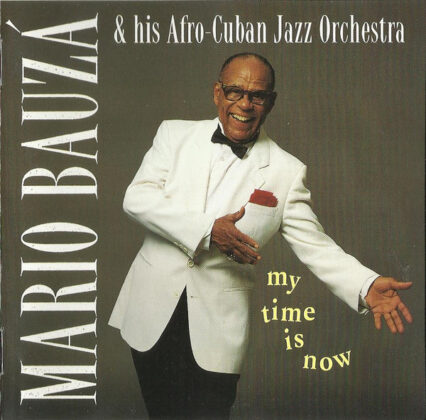

When back in the 1940s, trumpeter, saxophonist, and bandleader Mario Bauzá began to experiment with jazz melodies over Cuban rhythms he wasn’t out to invent anything.

When back in the 1940s, trumpeter, saxophonist, and bandleader Mario Bauzá began to experiment with jazz melodies over Cuban rhythms he wasn’t out to invent anything.

He was playing his life.

He was also giving a sound to a profoundly American experience: the immigrant’s embrace of life in the new country while holding on to his roots.

The result was Latin jazz.

Mario Bauzá was a 16-year-old, classically trained black Cuban clarinetist when he visited New York in a recording date in 1927, heard the Paul Whiteman Orchestra, and fell in love with the sweet sound of saxophonist Frankie Trumbauer.

“I went to all four shows, morning to night. I came out crazy,” he once told me.

Right then and there he decided to pick up the saxophone. Soon after he was back in Cuba, he left his job with the symphony orchestra and dedicated himself to playing exclusively jazz.

But while in New York, Bauzá had been also deeply affected by the vitality of Harlem, the dignity with which black Americans carried themselves, and what he saw as opportunities unthinkable for him under the racism prevalent in Cuba.

Those feelings also stayed with him.

In 1930, after being denied a job at a club in Havana for racial reasons, he left Cuba and moved to New York.

He said he was well aware of the racial conditions in the United States “but at least it was upfront and also there was a feeling of solidarity among [American] blacks that we didn’t have.”

He taught himself to play trumpet and found work with some second rate jazz orchestras. It was while playing with one of these bands at the Savoy ballroom that drummer and bandleader Chick Webb, then leading one of the best swing bands in the country, heard him play and was impressed.

Within six months, when Webb lost a trumpeter to Duke Ellington, he called on Bauza.

Fifty years later, Bauzá, who died on July 11, 1993, was still fond of telling the story of how, at the end of his first night at the job, at two in the morning, Webb approached him and asked him to come back in a few hours. “He told me ‘We usually rehearse at dawn. That way nobody misses a rehearsal,”’ recalled Bauza. He went out to eat and when he came back the orchestra was gone “and Chick told me ‘No, [this rehearsal] is for you,’ so I said ‘ Listen, I don’t want to waste your time. This shows me I’m not what you need,’ and he said ‘You’re wrong. You’ve got what you need and I have what you need.’ You have a great sound and a great concept but don’t know the accents of black American music. We both speak English but we have different accents. I’ll teach you.’ And he did, little by little.”

A year later, Bauzá was Chick Webb’s music director.

He stayed on five years before moving on to join Cab Calloway. Soon after, he maneuvered Calloway to hire his friend, a talented trumpeter with a reputation as a troublemaker, Dizzy Gillespie. It was Bauza who taught Gillespie about Cuban music. It was also Bauza who, when Gillespie decided he needed a conga drummer, recommended “Chano” Pozo, starting one of the most remarkable, if short-lived, partnerships in jazz.

He stayed on five years before moving on to join Cab Calloway. Soon after, he maneuvered Calloway to hire his friend, a talented trumpeter with a reputation as a troublemaker, Dizzy Gillespie. It was Bauza who taught Gillespie about Cuban music. It was also Bauza who, when Gillespie decided he needed a conga drummer, recommended “Chano” Pozo, starting one of the most remarkable, if short-lived, partnerships in jazz.

Mario Bauza (left), Marco Rizo, composer of the theme music for “I Love Lucy,” and Dizzy Gillespie; at Bauza’s 80th Anniversary Celebration at Symphony Space in Hall in 1991

It was also while with Calloway that Bauzá, tired of hearing Cuban music criticized as “hillbilly music” decided to form “a Latin orchestra that would sound like an American orchestra.

In 1940 he called on his childhood friend and brother-in-law Frank “Machito” Grillo, hired some of the arrangers he had worked with while with Webb and Calloway, and organized Machito and his Afro-Cubans, a band that still remains the high watermark for Latin big bands.

The original Machito band featured three Latinos, all in the rhythm section. “The rest were Italians, Philipinos, Black Americans, Jews,” he told me. “It was a rainbow orchestra.”

Bauzá’s heard the music — a blend of blues, big band jazz arranging, and old Afro-Cuban rhythms — as “a marriage. Each [music] preserving its identity but walking together.”

He called it Afro-Cuban jazz. It came to be known as Latin jazz.

It changed the sound of American music.

This essay was published by The Washington Post