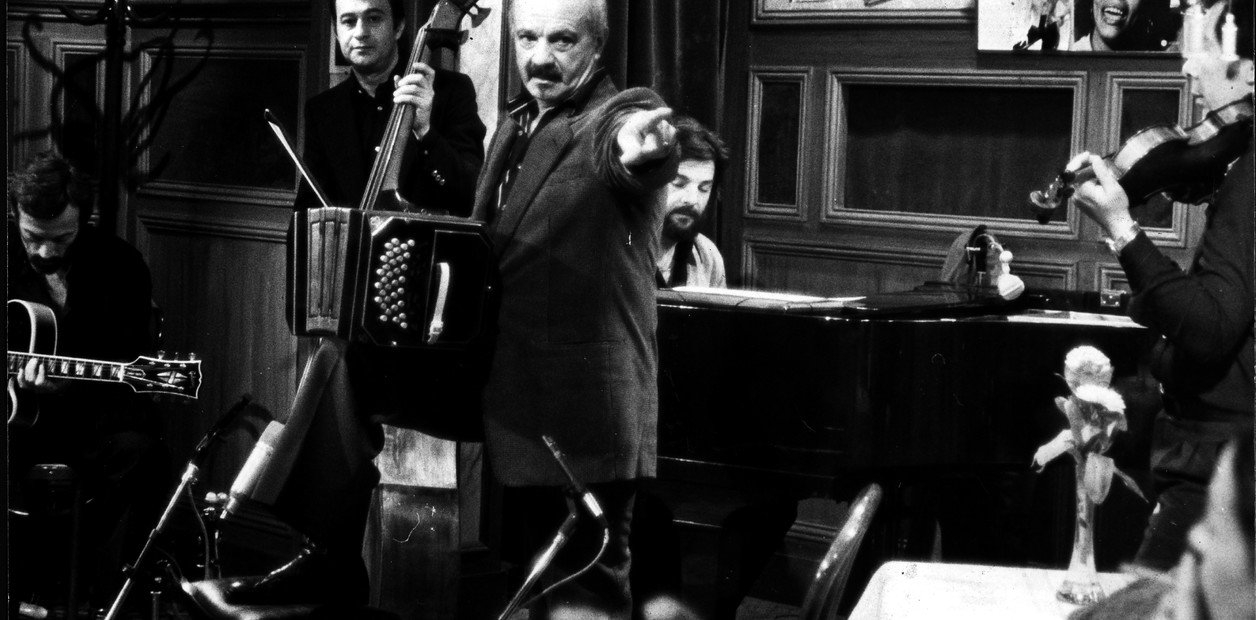

Astor Piazzolla (center) leading his quintet, perhpas his best instrument. Oscar Lopez Ruiz, guitar; Hector Console, bass; Pablo Ziegler, piano; and Fernando Suárez Paz, violin.

Argentine composer, musician, and bandleader Astor Piazzolla, the creator of New Tango, would have celebrated his 100th birthday this March 11.

He died in 1992 at the age of 71. But by then, his music — which rewrote the rules of tango by drawing from sources as disparate as jazz, European classical music, and klezmer — had made him an international figure.

Once reviled by many at home, Piazzolla attracted audiences for New Tango around the world and gained admirers and champions such as Mstislav Rostropovich, Yo-Yo Ma, Gil Evans, Al DiMeola, Gary Burton, and Grace Jones.

Also, as a student of classical music by day and a tango musician by night, the young Piazzolla had once dreamed of becoming a classical composer in the European tradition. But instead of merely emulating his predecessors, he forged a new musical genre that built on the foundation of the past. Years later, Piazzolla got to lead his ensembles in the temples of classical music, and his New Tango was played by symphonic orchestras, chambers groups, and string quartets. Being Piazzolla was enough.

Sometimes an outsider is needed to upend traditions and challenge entrenched habits — and Piazzolla, who was not born in Buenos Aires, the tango capital, but Mar del Plata, a seaside city about 248 miles south of Buenos Aires, and then grew up in the rough Lower East Side of Manhattan until the age of 17, was the perennial outsider — by fate and by choice.

He got his first bandoneon, the melancholy-sounding button squeezebox when he was nine, as a gift from his father, a tango fan. There was not a choice of bandoneon teachers in New York in the 1920s, so he made do by trying the buttons and, eventually, adapting the music by Bach and Schuman he learned from his neighborhood teachers, all pianists.

When the family returned to Argentina, he didn’t speak Spanish that well. “My mom would speak to me in Spanish, and I would answer in English,” he once told me.

Yet when Piazzolla moved to Buenos Aires, he soon found work playing and arranging for Anibal Troilo, a master bandoneonist and composer who led one of the top tango orchestras of the day. But still, in the tango world, Piazzolla was a talented oddball. And even Troilo was not enough for him musically. He started studying with classical composer Alberto Ginastera, organized his own orchestra and wrote music for film.

In 1954, when he was 33, Piazolla won a scholarship to study in Paris, France, with the fabled Nadia Boulanger, teacher of Aaron Copland, Darius Milhaud, and Elliot Carter, among many others. She was lukewarm about his classical writing, but, years later, Piazzolla was still fond of recalling the scene when she asked him to play something else, whatever he did back home. A bit mortified, he started out with “Triunfal,” one of his tangos, and after a few bars, she stopped him. “Now, this is Piazzolla,” she told him. “Don’t ever leave him.”

A version of this essay appeared in JAZZIZ Magazine.