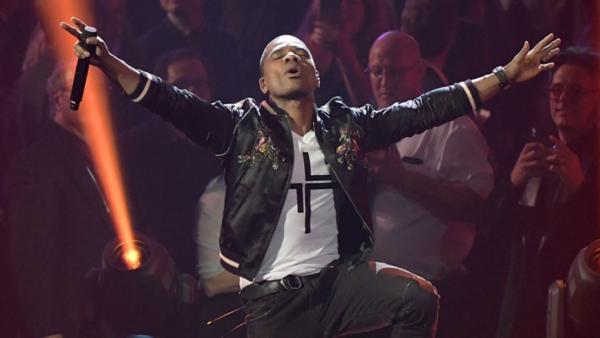

Gospel superstar Kirk Franklin

The song starts in the low register, like a rumble. It rises in pitch and volume ever so slowly, growing from a murmur to a visceral roar. Then shadings in the harmonies become lighter, luminous, dusk turning to dawn.

Someone cries out in praise. Others stand up, eyes closed, palms up. A woman in an African robe rises slowly as the choir sings, now loud, bright, in full voice: You are the source of my strength. You are the strength of my life. She extends her arms up and then back and opens her hands – I lift up my hands in total praise to you – then tilts her head back, eyes closed, as if bathing her face in the sound.

Such images of faith and devotion at the Bethel Full Gospel Baptist Church in Richmond Heights, mirrored inside black churches everywhere, are in part a testament to the power of gospel. With its spiritual weight, emotional range, and deep community roots, this is a music of unmatched grace, power, and beauty.

Forget the hip South Beach club of the minute or the hot producer of the month.

Week in and week out, the best music happens on Sunday morning, in churches large and small across South Florida.

The faithful have always known. Now millions of others, here and around the country, including many who have never set foot in a black church or opened a Bible, are discovering it – especially as a new generation of gospel singers, composers and producers are blending in street-smart beats of hip-hop, putting the old messages to a new sound, further blurring the line between secular and religious.

The results have been a commercial and artistic success – although controversial among many of the devoted. Gospel not only ranks among the fastest-growing forms of music in terms of sales; a song by singer Kirk Franklin, one of contemporary gospel’s biggest stars, has been nominated for Song of the Year in this year’s Grammys. It is the first time that a gospel song is up for such honors.

It is about time.

Largely ignored by mainstream media, often hidden in plain sight even to students of urban culture, gospel music has long stood among the most significant expressions of African-American culture and the source of much that has become commonplace in American popular music. Its influence can be heard in the classic soul styles of Aretha Franklin and Sam Cooke in the ’50s and ’60s, but also in the

music of singers such as new-jack crooner R. Kelly 30 years later. Its rhythms and textures are at the core of our daily vocabulary of backbeats and emotions, harmonies, and cries.

It’s all there – and a message too.

Gospel in all sizes

“Gospel music is about spreading the good news,” says Glenn Lee, pastor of music at the Bethel Full Gospel Baptist Church. “All that we want to do is inspire someone through our song to come to Christ. Everything is done to uplift and build up to the word of God. But maybe people are hurting, they are having problems at home, financial problems, emotional, physical problems, and what we want through

the music soothes the heart.”

But “a lot of people that come to church are not saved,” concedes Lee. “Maybe they are visiting with a friend, maybe they are here because they saw a pretty girl they want to come to see . . . A lot of people don’t come to hear the word of God. Music is one reason they might come, and if we can just get them here, we know that something will be said that will reach them.”

Bethel has one of the best choirs in South Florida – befitting a suburban congregation of more than 3,000 members. The full choir features 90 singers and is backed by a tight band featuring organ, keyboards, electric bass, drums, and horns.

The pulpit is spacious and imposing. The sound system is of theater-quality, and a web of strategically placed small microphones hangs over the choir.

“Music sets the tone for worship,” says Bishop Carlos L. Malone Sr., senior pastor at Bethel. “It prepares people for the word of God.”

And so, means alone are not a true measure of great gospel music. At the small Church of God Tabernacle (True Holiness) in Liberty City, with a membership of less than 200, the two choirs, directed by Della F. Poitier, have about 30 members.

The accompaniment consists of a pianist playing an upright set against the wall on the pulpit, and an electric guitar player, stationed on the opposite side on the floor.

When musicians are available, electric bass and/or drums are added. The Tabernacle choir includes secretaries, a 911 operator, a psychologist, a seamstress, a lawyer, and a nurse. Melba Randolph-Pompey, director of the church’s Inspirational Choir, works as a representative in the medical claims office at Allstate. Guitarist Tommy Edwards, who anchors the music, is a mail carrier at

the Washington Avenue post office in Miami Beach.

“We do not audition, so you do have different degrees of quality among the singers,” Randolph-Pompey says with a shy grin. “I’ve had people coming and telling me, `I know nothing about singing. I just want to do it because I really love it,’ and when I see the effort, the desire, the spirit . . . I believe if you are committed, if you have a real desire to excel, you can do it.”

Edwards started playing as a kid – he was 8 or 9 when his father, an elder at the Tabernacle church, taught him “three chords and we just played those chords and made a song out of it.” He has never played secular music, and he doesn’t seem particularly interested in starting now. “Music for me has been always related to the church,” he says.

The Bethel choir includes elementary schoolteachers, a credit union service representative, several bank tellers, a computer analyst, and a paralegal, among others. Patrick Merit, the choir director, works as an executive assistant with the Richmond Heights Community Development Corp. Pastor Lee, an exceptionally gifted musician and considered a master of the pedal steel guitar, is receiving his

bachelor’s degree in music from Florida Memorial College. He hopes eventually to pursue a career in music.

“I will never sell God out, and I will always be a member of the church,” he says emphatically. “But as an artist, I’m very open.”

Edwards recalls how his late aunt, Sister Nellie Edwards Coke, although she was the main pianist in the church, “could only play in two keys, key of C and key of G. If you played in any other key she couldn’t play; you had to play in those keys.

She played very well but was limited.”

Many argue that the power of gospel is precisely such dedicated amateurs. At Tabernacle, perhaps because everything feels close, the dialogue between those in the pulpit and the congregation flows easily and is both passionate and joyous.

During service, some of the faithful, seemingly out of nowhere, produce tambourines. As the choir sings out, many in the pews stand and join in, singing along, shouting encouragement to the soloists and praises to the Lord until the emotion in the place is almost overwhelming.

Here the harmonizing is not as tight and smooth or the soloists as polished as, say, those at Bethel, but the spirit is almost palpable.

As Moaning Bessie Griffin explains in Anthony Heilbut’s classic study The Gospel Sound Good News and Bad Times, “It ain’t the voice. Sometimes somebody with the squeakiest voice can say what we want to hear.”

`Feels like angels’

Whether a large or small church, the commitment to the choir is not a light one. It means at least one rehearsal a week, up to two engagements during the week, weekend special services, including weddings and funerals – and, always, church on Sunday.

But for soprano Debbie Jones, who works at Miami-Dade County’s school credit union, singing in the choir “takes a load off me.”

“All the stress that you’ve gone through during the day, it’s a release,” she says. “When you come here and start singing you think about all the good things because praise God, you made it through another day.

When the choir is in full flight, “it feels like angels,” says Jones, who once recorded with Miami soul singer Clarence Reid. “That’s what it feels like and, most of the time, that’s what it sounds like. It just prepares you for what’s going to happen when we get to heaven.”

Jamaica-born Anthony Hawthorne, a tenor at Bethel, is a young veteran of the music business. As a lead singer and leader of Rough Cut Crew, he opened concerts for stars such as Shabba Ranks, Bobby Brown, TLC, and Mary J. Blige. But in 1995 Hawthorne “got saved, started to attend church and joined the choir shortly after that.” He had never sung in such a group before.

Hawthorne, who now has a music-production company, is hardly a starry-eyed novice, yet in trying to explain how it feels to be part of such sound he struggles for words. “It’s, it’s almost like a feeling of elevation,” he says. “Here you are surrounded by these voices – especially if you are standing in the front row, you feel all these voices coming from the back of your head, and it is huge. There comes a

time when you feel so overwhelmed that you feel almost like breaking out and doing your own thing – man, I have to shout, I gotta do something.”

Gospel’s new superstar

It is this power, this capacity to stir deep emotions, that is bringing to gospel new converts from well beyond the confines of the church. As a result, not only are the major labels acquiring small gospel labels and signing acts, but even rap labels such as Tommy Boy and Jive have gotten involved in gospel music.

The Nashville-based Christian Music Trade Association reported that for the third consecutive year, gospel showed an increase in sales. It now represents 6.3 percent of all the records sold by the entire music industry. The report cites SoundScan, a computerized service that collects data from actual sales at cash registers, in claiming that Christian music ranks fifth behind R&B, rap, country and

soundtracks and ahead of heavy metal, jazz, classical, Latin, and New Age.

“What’s happened,” says Datu Faison, gospel, rap and R&B chart manager for Billboard magazine, “is that gospel has broken somewhat into the mainstream. I take my hat off to Kirk Franklin because before him, for the most part, unless you were an R& B-flavored gospel act like a BeBe and CeCe Winans, who were gospel but sounded like R&B and didn’t say the word God . . . you were somewhat forbidden in R&B radio stations.“Franklin made it acceptable. He broke down a lot of the barriers, made it hip and cool.”

Born Kirk Smith and a product of the tough streets of Forth Worth, Texas, Franklin (he took the name of his church-going great aunt who adopted him at age 4 turned to God at 15 after the accidental shooting death of a friend. Blending the imagery and deep grooves of hip-hop with traditional gospel message, Franklin revolutionized the gospel industry while taking the music into unexpected places.

His single Stomp, for example, draws heavily from funkmaster George Clinton’s One Nation Under A Groove and a rapped section – except that the call and response between Franklin and his posse goes: “G.P. [God’s Property, the choir’s name] are you with me? Oh Yeah we having church we ain’t going nowhere!.” It played not only on gospel radio but urban stations. The video got airplay on MTV. In a business in which 100,000 album sales only recently constituted a major hit, Franklin sold almost four million records in fewer than four years.

The updating that Franklin and other contemporaries such as Fred Hammond and Hezekiah Walker have given gospel is only the latest evolution in the history of this music. After all, gospel as we know it developed as recently as the 1930s, by artists such as Thomas A. Dorsey, a blues singer who, as Heilbut writes in his The Gospel Sound, “consciously decided to combine the Baptist lyrics and Sanctified beat with the stylized delivery of blues and jazz,” and Sister Rosetta Tharpe, who at one time sang blues and “invented pop gospel.”

Thomas Dorsey, blues singer, and gospel pioneer

Gangsta backlash

Gospel found its way into popular music through the powerful voices of soul vocalists such as Aretha Franklin, Sam Cooke and Al Green as they took the phrasing, the cries, the pacing of emotion they had learned in church singing gospel and reinterpreted them in a secular context with secular lyrics. Because of this, gospel and R&B have long been presented as two sides of the same coin. In fact,

gospel music is charged with profound sensuality and passion.

Someone listening to Kirk Franklin’s lyrics in his Whatcha Lookin’ 4, might mistake them for just another secular love song: “I was searchin’/ For someone to love me right/ Hear me when I cry/Keep me late at night . . . Whatcha’ lookin’ 4/I’m the One you’re lookin’ 4.” Only a closer hearing – or a look at the printed lyrics – reveals that Franklin is actually singing about “the One.”

“This gospel thing did not grow overnight,” says Billboard’s Faison. “The roots of R&B are in gospel music, this has always been here but it has become acceptable, more popular and now it’s become kind of cool. Before, it was something your grandma listened to. But now, when you see young people who act like you and talk like you doing it, it makes it a little more acceptable.”

The audiences have always been there, says Tara Griggs-Magee, vice president and general manager of Verity Records, echoing a long-held belief among gospel fans. The “tremendous growth” in sales is due in part to “a lot better job as an industry in the marketing and positioning of our records,” she argues. “One of the biggest problems our consumers have had over the years is just finding the music.”

And of course, there is the allure of the message. After years of negativity and

violence exemplified by gangsta rap, “there was a hunger and a need, and gospel is filling that void.”

In fact, many in the industry agree, some of this newfound interest in gospel among artists and audiences is a backlash against gangsta.

“Most of these R&B singers grew up singing in the church anyway,” says Faison. “They grew up singing gospel music, and somewhere along the way the dollars called, their tastes changed, whatever, so they moved to R&B. But their roots are in the church, most of them still remain spiritual.’

Griggs-Magee concurs, saying that the love of God they once learned in Sunday school continues to live in their work. “It is at the roots of their music. They grew up singing in the choir. And now, with the exposure gospel music is getting, people feel they are going back home to their roots and still have a connection to the church.”

But while people like Griggs-Magee would argue that putting God’s message to a hip-hop beat might be a way to reach a young audience that otherwise might not listen, many traditionalists object.

“Yes, you have to reach the young people, but God has never lowered the standards for anybody, so there is a certain standard you have to maintain,” says Randolph-Pompey, the Inspirational Choir director at the Church of God Tabernacle in Liberty City. “Just because [churches want to attract] Generation Xers with their baggy pants and their hair sticking out, you don’t have to lower the standard. I think they are getting the wrong perception of what this is all about. Are you really feeding them the word of God?”

But Bishop Malone of Bethel in Richmond Heights, who prefaces his response by saying he is a personal friend of Franklin, takes a more pragmatic approach.

“I say change the method but never change the message,” he says with a shrug. “The message has to stay the same, but if we are going to reach everybody how we present our theology must change. Kids nowadays are into rap . . . so we can take gospel music and rap it and reach that audience . . . We have to be sensitive to that and open to change.”

He recalls the opposition he found when he first tried to change the sound of the music at Bethel to a “more contemporary flavor,” bringing in electric instruments and a different, contemporary repertoire.

“Oh man, was there resistance,” he says. “But I established one principle when I came to this church [in February 1990], and that was that everything had to be done according to the word of God. And the Bible says, `Praise Him with the sound of the trumpet, Praise Him with the psaltery and the harp, Praise Him with the timbrel and dance, Praise Him with stringed instruments and organs, Praise Him upon the loud cymbals, Praise Him upon the high sounding cymbals. Let everything that hath breath praise the Lord.’

“Now, that’s Psalm 150. You can’t argue with that.”

This story was published in Miami Herald February 1999