Masterpieces spark new work. Piazzolla in Brooklyn was inspired by a dreadful recording.

Masterpieces spark new work. Piazzolla in Brooklyn was inspired by a dreadful recording.

Take Me Dancing, a 1959 jazz tango album by New Tango master Astor Piazzolla, was dreadful. Astor Piazzolla said so.

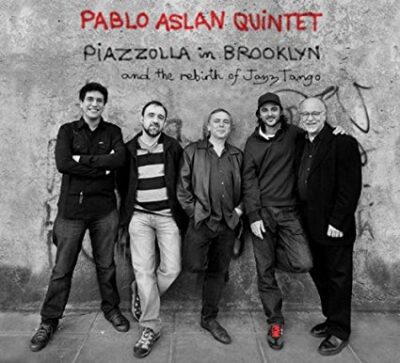

Still, Pablo Aslan was curious. Aslan, an Argentine-born, Brooklyn-based bassist, bandleader, and producer, has been a pioneer in jazz tango, working on his own ideas for the past 20 years. His 2009 Tango Grill, a recording that looked at jazz tango through a traditional tango keyhole, earned him GRAMMY and Latin GRAMMY nominations.

“I had heard all the infamous stories about this recording, so when I saw Take Me Dancing in a record shop in Buenos Aires, I snatched a copy,” he says. “And it played exactly as I expected: it was awful. It was just as Piazzolla had presented it.”

There was little jazz and a simplified, clunky Piazzolla played to a guiro-and-bongo beat.

But then Aslan read a critical reevaluation of Piazzolla’s career (Diego Fischerman and Abel Gilbert’s study “Piazzolla El Mal Entendido,” Piazzolla The Misunderstood) and the comments about Take Me Dancing intrigued him into giving it an open-minded second listening.

What he heard then inspired Piazzolla in Brooklyn.

“The themes and the ideas were very strong and original, but some of them just went by too fast,“ he says. “I felt there were many places where the music could be opened up and developed further. That was the Eureka moment, when I realized that the material in this record had a potential that just needed to be unleashed.”

The transcriptions of the original arrangements by Piazzolla for nine of the pieces in Take Me Dancing became the road map for Piazzolla in Brooklyn. And for the journey, Aslan not only had Piazzolla as a guide, but also something that el maestro didn’t have: a group of musically bi-lingual players (including Piazzolla’s grandson, drummer Daniel “Pipi” Piazzolla), as knowledgeable and comfortable with the vocabulary, syntax, and rhythms of tango as they are with jazz.

The Piazzolla of Take Me Dancing was a musician desperately juggling artistic ambitions and subsistence needs. He was back in New York City, where he had spent most of his childhood, but now with a wife and two kids, and looking for a fresh new start for a sputtering career. (“La Calle 92,” the only track here that is not from Take Me Dancing, plays like scene setter. It’s a piece by Piazzolla titled after the street where he and his family lived during this period.)

He pushed and probed, but with modest success. His most ambitious gambit was “a new rhythm called J.T. (jazz tango), “ Piazzolla wrote in a letter dated June 1958 that Aslan found in his research. “This rhythm has been well-liked because I play jazz melodies with a modern tango rhythm. It’s the only way to break in the U.S.A.”

The pearl of this work was supposed to be Take Me Dancing, a recording of both originals and jazz standards interpreted by his Jazz Tango Quintet, comprising electric, guitar, vibes, piano, and bass, plus small percussion. Dominican bandleader, musician, and producer Johnny Pacheco, who would go on to develop salsa and cofound the influential Fania Records, was one of the percussionists in the Take Me Dancing sessions. “I had no idea who [Piazzolla] was,” Pacheco told me. “I was doing a lot of studio work those days and they called me because I could read music. Everything was written down. It was tango with rhythm, and he improvised in jazz [style].”

“It was the first time I had ever heard a bandoneón played in that style,” he recalled. And Piazzolla, “had this expression of happiness in his face because everything he had written, he was hearing. These were the best studio players around. As for me, it was a feast.”

In August 1959, in another recently unearthed letter, Piazzolla writes his friend that “The recordings are marvelous, and if the company really tries, they will sell well.”

In fact, Take Me Dancing sank without a trace. Piazzolla would later sour on the whole experience, and go on to denounce the quintet as “a monstrosity,” and Take Me Dancing as an artistic “sin.” In those recordings, he once said, “I sold my soul to the devil.”

Daniel Piazzolla, a musician himself, remembers asking his father about Take Me Dancing “seven million times, and the conversations always ended the same way: with him yelling at me, ‘don’t bust my chops with that piece of shit, that crap, that black stain in my story.’ “

Yet for all its shortcomings, real and exaggerated, an argument can be made that Take Me Dancing had a subtle but lasting impact on Piazzolla. Still, while he would go on to collaborate with exceptional jazz musicians such as Gerry Mulligan and Gary Burton, Piazzolla never went back to jazz tango.

As it turned out, that was left to another Argentine New Yorker, one raised in Buenos Aires but educated on Miles, Coltrane, and Mingus, as well as Salgán, Pugliese, and Piazzolla.

“Astor Piazzolla has been a model for my own development, but I also had systematically avoided his music,” Aslan told me. ”I always felt it was too strong and defined, and his own interpretations very rarely have been surpassed. But in Take Me Dancing I found a place where I could create my own world and actually interact with him.”

That place is Piazzolla in Brooklyn. This project is not a remake and it’s not nostalgia. It’s not even a tribute. Rather, it’s a continuing conversation among musicians, across fifty-odd years of music, shared stories of displacement, and deeply personal searches.

It’s a thank you note to a favorite teacher, long gone: your lessons were not lost on me, on us.

It has all been worthwhile — and we are carrying on.

Fernando González was nominated to a GRAMMY © for Best Liner Notes for these notes.