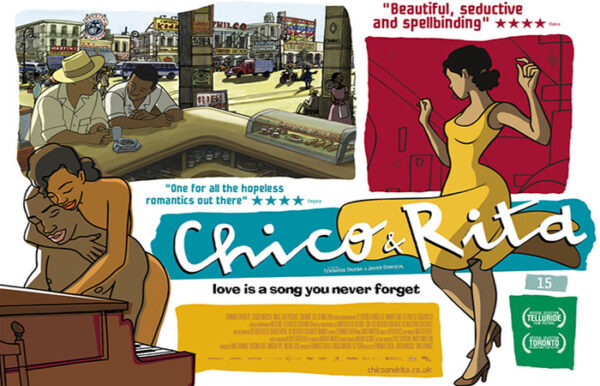

Chico & Rita, the Oscar-nominated animated film by the Spanish team comprising Academy winner director Fernando Trueba, illustrator Javier Mariscal, and director Tono Errando, is being released in a Limited Edition Collector’s Set including Blu-ray and DVD discs, an audio CD and a 16-page excerpt from the graphic novel based on the film. (A DVD single is also available.)

Chico & Rita, the Oscar-nominated animated film by the Spanish team comprising Academy winner director Fernando Trueba, illustrator Javier Mariscal, and director Tono Errando, is being released in a Limited Edition Collector’s Set including Blu-ray and DVD discs, an audio CD and a 16-page excerpt from the graphic novel based on the film. (A DVD single is also available.)

Likened by Trueba to a bolero on film, Chico & Rita is, on the surface, a standard boy-meets-girl, boy-loses girl, will boy get-girl-back? movie. It starts in the late 40s, and tells the love story between a pianist and a singer, following them through their early struggles, success, heartbreak, and final triumph from their native Havana, Cuba, to New York, Las Vegas, and back.

But the real subject of Chico & Rita is the music.

“The love story is the McGuffin [a plot device], a pretext to tell the history of the music of those days, the rise of bebop, the rise of Afro-Cuban jazz,” says author and producer Nat Chediak, who wrote the Dictionary of Latin Jazz, which Trueba edited, and is a long time friend and collaborator of Trueba. For Chico & Rita Chediak collaborated with Cuban composer, arranger and guitarist Juanito Márquez on the lyrics of “Lily,” a key song in the plot of the movie.

While dedicated to the great Cuban pianist, arranger, and bandleader Bebo Valdés, the film is not The Bebo Valdés Story, says Trueba, speaking from his home in Madrid, but “a composite of the stories of many Cuban musicians in the 40s. We created a character that is not Bebo, but has a lot of him.”

In fact, in explaining the dedication to Valdés, Trueba wrote in his liner notes that “It could be no other way. Had I not met Bebo, Chico & Rita would not exist. He was our inspiration.”

Chediak, who was close to the process, adds “ Mariscal drew the character as an approximation of Bebo. There are no ifs or buts about it. Mariscal’s character was Bebo.”

The relationship between Valdés and Trueba dates back to El Arte del Sabor, a trio recording featuring Bebo´s childhood friend, bassist Israel Lopez “Cachao,” and conguero Patato Valdés (no relation) and Calle 54, Trueba’s film about Latin jazz, both completed in 2000. The decade that followed encompasses what Trueba refers to his “Bebo Years.”

In that period, there were several albums — including Lágrimas Negras the improbable international hit with flamenco singer Diego el Cigala, the tour de force Bebo de Cuba and the emotional Juntos Para Siempre, the duet recording of Bebo and his son Chucho Valdés. They earned Valdés, Trueba and Chediak multiple Grammys and Latin Grammys.

In that period, there were several albums — including Lágrimas Negras the improbable international hit with flamenco singer Diego el Cigala, the tour de force Bebo de Cuba and the emotional Juntos Para Siempre, the duet recording of Bebo and his son Chucho Valdés. They earned Valdés, Trueba and Chediak multiple Grammys and Latin Grammys.

And Valdés also went on to appear in a couple of Trueba films — including a cameo in The Shanghai Spell (2002) and playing himself in a leading role in The Miracle of Candeal (2004).

In Chico & Rita, with one exception, when Chico plays we are listening to Bebo Valdés. In all likelihood, it was his final performance.

In Chico & Rita, with one exception, when Chico plays we are listening to Bebo Valdés. In all likelihood, it was his final performance.

“Knowing Bebo has been a gift for me, one of life’s gift,” says Trueba. “And I believe it has been a very happy collaboration for him because he has felt again the affection of the public, he has played at sold-out theaters around the world, he has made some money. For 10 years we didn’t stop working together, and all culminated in Chico & Rita.”

After completing the film, Bebo Valdés, who will be 94 on October 9th, effectively retired. (N.Ed. Bebo Valdés died a few months later, on March 22, 2013)

For Chediak, who has shared in much of their time and work together, “Even if you don’t know the special relationship between Bebo and Fernando, which is almost that of a father and son, I think it’s virtually impossible to watch this film and not see it as a loving embrace of the man and his music. By the end, the dedication to Bebo is almost unnecessary.”

As Trueba underscores, the story not only pays tribute to Valdés but also to other pioneering Latin musicians such as Mario Bauzá, Machito, Chano Pozo, Tito Puente, Miguelito Valdés (no relation), and Cachao. Chico & Rita´s tale of fame-to-oblivion-and- back, alludes not only to Valdés, who was forgotten and playing hotel lounges in Sweden before Paquito D’Rivera came calling in 1994 and jump-started the final chapter of an extraordinary career, but also those of musicians such as Cachao (who was for a time making do playing quinces parties and bar mitzvahs in Miami) or pianist Rubén Gonzalez (rescued from obscurity by Buena Vista Social Club.)

Notably, rather than relying on historical albums, Trueba had the music re-recorded.

Using the old recordings would have made yet another compilation, “and that would have been uninteresting,” he says. “Those who love Charlie Parker or Dizzy or Chano Pozo already have their records at home. What’s the point of making a movie for that? Re-creating it was a much better challenge.”

The new versions were recorded by three different bands in Havana, New York and Madrid. Valdés arranged and conducted the smaller Madrid band, Jorge Reyes played that role in Havana and Michael Mossman arranged and directed the New York orchestra. (The soundtrack also includes tracks from Bebo de Cuba and Bebo)

“So when you hear a Bebo composition, it’s him on piano, even the new versions of them,” says Chediak. “In the updated version of ‘Con Poco Coco,’ [Valdés’s piece from the groundbreaking Cuban jam session in 1952] that’s him on piano.”

And the music scenes also include cameos by jazz icons such as Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Parker, Nat King Cole and Ben Webster, interpreted by living musicians playing in character. Freddy Cole “appears” as his brother Nat, Jimmy Heath becomes Ben Webster, Mike Mossman plays Dizzy, Yaroldi Abreu becomes Chano Pozo and Germán Velazco takes a turn as Charlie Parker.

“Once we decided that we were going to include the moment when jazz meets Cuban music that led us to the idea of including Chano Pozo as a character in the plot and mix truth and fiction and include the cameos,” says Trueba. “We had a great time playing around with all that.”

Still, he says, “I was concerned that the musicians would be offended by me asking them to ‘play like.´ But they understood what we were doing, they embraced it, and it was great fun.” In some cases, the results were dramatically successful.

“I remember Paquito [D´Rivera] coming out after watching the movie and asking me ‘Who the hell plays Dizzy? It’s perfect,” recalls Trueba. And he tells the story of how, a few months after the sessions, Valdés was visiting him at his home and the film’s soundtrack was playing in the background. “And we were talking and when ‘Con Poco Coco’ comes on, Bebo stops in midsentence and says ‘Listen. That’s [trumpeter] El Negro Vivar’,” recalls Trueba with a chuckle. “And I had to tell him that actually that was the new recording and that was Carlos Sarduy.”

“I remember Paquito [D´Rivera] coming out after watching the movie and asking me ‘Who the hell plays Dizzy? It’s perfect,” recalls Trueba. And he tells the story of how, a few months after the sessions, Valdés was visiting him at his home and the film’s soundtrack was playing in the background. “And we were talking and when ‘Con Poco Coco’ comes on, Bebo stops in midsentence and says ‘Listen. That’s [trumpeter] El Negro Vivar’,” recalls Trueba with a chuckle. “And I had to tell him that actually that was the new recording and that was Carlos Sarduy.”

After completing the film, and before the official premiere, Trueba traveled to Málaga, in the South of Spain where Valdés now lives, and rented a movie theater to show it to the maestro and to flamenco singer Estrella Morente, who stars as herself in the movie and, as it turns out, also lives in that city.

“Bebo came with Rosemarie [his wife, who has since passed] and Estrella with her husband, Javier. And the four watched in the empty theater and at the end, they are all crying. I had never seen Bebo cry. And when he sees me, he kisses my hand and hugs me and says ‘It’s that when I’m gone, the people will still watch this movie and will hear my music.’ And that’s when I understood that for Bebo, as a musician, that was the greatest gift of this movie. For me, that was a moment of pure happiness that I’ll never forget.”

This feature appeared on the October 2012 issue of JazzTimes