The city of Salta — the capital of Salta province in northwest Argentina — is about a thousand miles and a world apart from Buenos Aires, Argentina’s urbane, Europhile capital. Campo Santo is a small town about 37 miles north of Salta. In the 1930s, the town had no electricity. There was no radio, no records to play.

The city of Salta — the capital of Salta province in northwest Argentina — is about a thousand miles and a world apart from Buenos Aires, Argentina’s urbane, Europhile capital. Campo Santo is a small town about 37 miles north of Salta. In the 1930s, the town had no electricity. There was no radio, no records to play.

And yet, Timoteo “Dino” Saluzzi, born in Campo Santo on May 20, 1935, came to play the bandoneón — a button squeezebox invented in Germany during the mid-19th century. Created as a poor man’s harmonium for countryside religious services, the bandoneón later became the quintessential tango instrument in the whorehouses of Buenos Aires, half a world away. During the course of his improbable career, Saluzzi brought the bandoneón back to Germany.

And on his recently released Ojos Negros (ECM), with German cellist Anja Lechner, Saluzzi reclaims the sonorities and feel of its religious origins and brings them all back to Campo Santo. For Saluzzi, moving forward has often meant circling back.

He began his career in the 1940s, playing traditional Argentine folk music and tango — genres that feature tightly formatted songs, unambiguous harmonies, and a strong, definite pulse. Throughout this early period, Saluzzi approached music rather conventionally, while burnishing a sound that was at once poetic and gruff. Over time, he deconstructed his style of writing and playing, adding pop, jazz, and even classical elements to his work. That sound, best represented on Saluzzi’s ECM recordings, retains a mysterious, evanescent quality. These days, Saluzzi’s song forms — even the pulse of his music — are often implied rather than clearly stated. Harmonies form and dissolve like clouds of smoke; melodies often suggest unfinished thoughts and fragments of whispered conversations. Little, if anything, unfolds linearly or resolves neatly or happily. Listening to him on disc, it’s difficult to discern what is composed and what is improvised. And yet the music not only has its own logic, it also possesses a certain grit and earthiness. To Saluzzi, all of it — the old and the new — is of one piece.

“When I hear the old records, what I feel is that I have not changed,” he says, his Spanish still paced by the cadences of his native Salta. “I’ve acquired more experience, but I remain in love with simplicity, directness. Sometimes I feel a bit embarrassed seeing how everything I do is so simple. But what can I do?”

Simple though they may be, some pieces on Ojos Negros seem to have been thought out programmatically. In the liner notes, Steve Lake writes that “Carretas” conveys the movement of oxcarts in the Pampas, and “Esquina” is a “re-enactment of a late-night scene after dark in Salta, more than 60 years ago.” On “Minguito,” Saluzzi pays tribute to a TV character portrayed by an Argentine comedian. But for all the disparate sources and allusions, Saluzzi says that all the songs are rooted in and bound by a certain spirituality. “Even ‘Ojos Negros’ has a religious character,” he says. “It looks behind the lyrics. It’s a tango written about a woman who works in a whorehouse. But beyond the circumstances, the accidents of life, there is humanity — and behind that, belief.”

In “Serenata” — perhaps the most notable example of the album’s religious tone — Saluzzi returns to some of his deepest, most personal memories. “I remember a time I was coming back home with my mom,” he says. “My mom was very, very religious. I don’t remember what I had done, but as punishment, she put me to pray to the Virgin Mary in our home altar. It was a small altar made of sheets of tin and cardboard figurines and some natural blue flowers. And I never forgot that scene.”

In “Serenata” — perhaps the most notable example of the album’s religious tone — Saluzzi returns to some of his deepest, most personal memories. “I remember a time I was coming back home with my mom,” he says. “My mom was very, very religious. I don’t remember what I had done, but as punishment, she put me to pray to the Virgin Mary in our home altar. It was a small altar made of sheets of tin and cardboard figurines and some natural blue flowers. And I never forgot that scene.”

Saluzzi speaks of his first house as “una choza,” a hut, with a dirt floor. The area was home to many Italian-immigrant families, and with them came the bandoneón. Saluzzi’s father, Cayetano, the son of one of those immigrant families, was a day laborer in the sugarcane fields and an amateur musician who played guitar and mandolin and bandoneón. Growing up, Dino was always near music and that odd squeezebox with all those buttons.

“But that’s the rational answer [to how I began playing bandoneón],” he says, pausing. “Nowadays, everything seems to have an explanation — but I believe some things cannot be explained. I believe things and people have a destiny, and the nicest thing is to fulfill that destiny. That’s what I call [i]el viaje[i], the trip. And inanimate objects, like musical instruments, also have their trips.” Then with a sigh, as if explaining the obvious, he adds, “The bandoneón came to get me and take me away.”

At 7, Saluzzi began taking music lessons from his father. “Working the fields was hard work, and he didn’t want me to do that,” Saluzzi recalls. “He wanted something else for me. And he pushed me. He would say, ‘I go to work to the field, your work is to study, to practice.’” In those days, he remembers, “The bandoneón was like a toy. I had it always, always with me. I was always around it.” By the age of 14, Saluzzi was playing in a professional trio. Not long after joining the group, however, he moved to the city of Salta.

“Sixty kilometers [37 miles] in those days was a world away,” Saluzzi says. “But in these small towns, there were not many opportunities for a musical education. If now we are beginning to catch up, imagine what it was like 60, 70 years ago.”

“My first exile was from that small village, leaving Campo Santo to go to Salta. It broke my heart because who doesn’t want to live where he was born? From that moment on, the instrument marked me. I’m always gone. I’m never of the place. And you can’t go back. If you do, you find that whatever was, it’s not there anymore.”

As it turned out, Salta proved too provincial for Saluzzi, so, at 17, he moved to Buenos Aires. It’s always been hard for a man “del interior” (of the countryside) to find his way around in Buenos Aires. The city’s mostly closed music world is especially forbidding. Saluzzi still gratefully recalls the help he received from veteran musicians such as bandoneónist and arranger Julio Ahumada, who became one of his teachers, and especially from bandoneónist Ciriaco Ortiz, one of the great players in tango history. By Saluzzi’s estimate, Ortiz’s accomplishments in tango are equal to those of Louis Armstrong’s in jazz. “Everything that can be played in tango on the bandoneón, Ciriaco played it. It’s already all there.”

In Buenos Aires, Saluzzi began playing in different orchestras — such as the one led by violinist Enrique Mario Francini — and the groups of tango violinist Alfredo Gobbi and singer Héctor Varela. He continued taking lessons and read about “things I thought I’d eventually need. My learning was very atypical,” he remarks.

Eventually, Saluzzi joined the Orquesta Estable de Tango de Radio El Mundo, the house tango orchestra of a major national radio station. “Those days, there were many orchestras in the radio stations, and each orchestra had its own personality and distinct sound,” he recalls wistfully. “Radio El Mundo had a symphony orchestra, a light-music orchestra, a tango orchestra, and a jazz orchestra. It was remarkable. And we played every day. It was fantastic training. We got to be so comfortable with the rhythmic patterns of tango that we didn’t even rehearse; we just looked at the lines on the sheet, saw the contour of the lines, and played. And every day we played a different type of music. You really learned. But the older musicians would tell me: ‘Kid, you need to study. You need to talk to so-and-so, see so-and-so.’”

In the early 1950s, Saluzzi remembers, Buenos Aires was enjoying “an explosion of ideas. It was such a rich time in culture, not only in music, but in literature, film, art, fashion.” During that time he met bandoneónist, composer, and bandleader Astor Piazzolla, master of New Tango, a radical update of traditional tango. By then, Piazzolla, who had paid his dues playing traditional tango, was already known among musicians, but far from popular.

“He was still playing in small joints,” Saluzzi says. “I remember seeing him at the Jamaica [club], a place of seven tables in [i]el Bajo[i], [an area of Buenos Aires near the port that was a cross between a red-light district and a bohemian hangout]. We talked a bit. He was a fighter but also a great worker.” The two musicians would meet again over the years. During one of those meetings, Saluzzi told Piazzolla how he had been criticized for his unorthodox approach to the bandoneón. Piazzolla’s response, Saluzzi recalls, was simply: “You have to go. You just have to go.”

In 1956, Saluzzi did leave, but only to return to Salta. He wanted to develop his own compositions, his own brand of folk music. He didn’t remain for long. “I stayed for one or two years; I don’t really remember. But I had caught the bug, and it was impossible [to stay]. The circumstances were not appropriate to grow. I began to feel more and more uncomfortable until I had to leave. I had come back afraid of the big city. I wanted to recapture my childhood, my puberty, but when I went back, it wasn’t there.”

Saluzzi is about 5 feet 10 inches tall, stocky, broad-shouldered, and bullnecked. His appearance suggests that of a small linebacker, and in fact, he still moves with the slowness and easy grace of a former athlete. He speaks unhurriedly also, gently. Now and then the excitement of an idea, a certain argument, results in a quick, uninterrupted line, but for the most part, he paces himself with small pauses. In conversation, as in his music, his ideas often take circuitous courses. They demand time, patience, and active listening, but the rewards are many.

Back in Buenos Aires in the late ’50s, he stopped playing bandoneón for nearly eight years. “It’s so stupid that I’d rather not talk about it,” he says. “It was a childish thing. Chalk it up to immaturity.” When pressed, he hints at frustration with the music world. And so for a while he became a salesman, hawking hairspray on buses. But eventually, he got a job, playing percussion in the police’s symphonic band, which was in the process of adding strings and becoming a symphony orchestra.

“I was still studying and I knew the classics, the romantics. I had studied conducting and read about form, counterpoint, orchestration, Vienna in the 1920s. I read a lot,” he says. “And this was the first time I was inside an orchestra. And because I couldn’t do anything else but I was able to read music, they put me to play percussion. But for me to count bars [and wait for my part to play] was impossible because once I started to listen to what happened around me, inside that orchestra, I was like hypnotized, paralyzed of beauty. Now, don’t misunderstand me, it wasn’t the Berlin Philharmonic. In fact, it was lousy, but for me, it was another step towards art music. Now I realize, and get goosebumps about it, how destiny put me in front of new music in some odd ways.”

Recalling those days, he chuckles because it was, after all, a police band, and all the players had police ranks — officer, inspector, detective, and so on. In bureaucratic terms, Saluzzi had the lowest rank: agente, a street cop.

His work with the symphonic band (which came to include writing, arranging, and even conducting), the innovations of Piazzolla, and the music whirling around him in Buenos Aires (he recalls hearing the jazz standard “Laura” on bandoneón, possibly by Piazzolla) had a profound impact on Saluzzi, who resolved to do other things with the bandoneón besides playing tango. He liked jazz, discovered Bill Evans, and found that “with difficulty” he could imitate jazz pianists on the bandoneón. He wrote new music, put together his own group (comprised of some of the best jazz musicians in Buenos Aires), and recorded Soy Buenos Aires [“I am Buenos Aires”], a disc that’s now impossible to find.

The 1970s proved a momentous decade for Saluzzi. He practiced with jazz records and discovered contemporary music masters such as Luigi Nono, Carlos Chávez, Silvestre Revueltas, and Dmitri Shostakovich. He collaborated with Gato Barbieri, who was exploring Latin American roots music, appearing on the Argentine saxophonist’s 1973 release [i]Chapter One: Latin America[i]. But he also continued to make traditional folk music — even recording two albums with Los Chalchaleros, a classic folk group from Salta — and to work in tango orchestras. And he followed his jazz-group experience with a band of young rockers, with whom he recorded two discs Vivencias I and II.

And then George Gruntz walked in.

Gruntz, a pianist, composer, and bandleader who became president of the Berlin Jazz Festival was visiting Buenos Aires, looking for new talent. Jazz bassist Jorge “El Negro” González, the Ron Carter of the small but active Argentine jazz scene, recommended Saluzzi.

“He told him, ‘There is a guy who plays bandoneón but doesn’t play tango, doesn’t play folk music, doesn’t play jazz. It’s not clear what he’s playing.’ And Gruntz said, ‘That’s the guy I want to meet,’” Saluzzi recalls with a chuckle. “And, in fact, I told Jorge to not bring him to our rehearsal space because it was a dump, very depressing. Not a great place. But he came anyway.

“And suddenly there I was, before an orchestra [The George Gruntz Concert Jazz Band] with my instrument, which, at that time, nobody knew much about — and less so as a jazz instrument. I found myself in a big band that was like the United Nations, great musicians from all over the world — people like Palle Mikkelborg from Denmark, Seppo Paakkunainen from Finland, Sheila Jordan — and me with my bandoneón. When I put [the bandoneón] out, everybody came over to check it out and see what the hell was that,” he recalls, laughing. “It was incredible. I watched their faces and I was so scared. … But I had to work, to maintain my family so …” his voice trails off. “It turned out to be a tremendous thing.”

When Gruntz asked for original pieces for the band, Saluzzi submitted “El Chancho,” a piece he had recorded for [i]Vivencias I[i].

“We rehearsed. I was reading the lines without a problem, but then we came to the chord notation, and at one point it said ‘solo.’ And everybody stopped — and I stopped too,” he laughs. “I didn’t understand English, so I had no idea what was going on. They had to explain it to me, explain the chord notation, that that was where I played the solo, everything, and we got on. And I had a sort of a cadenza, and I let it rip. There I could really play who I was, and the guys [in the band] stood up and applauded. It moved me to tears.”

That experience with Gruntz opened the world to Saluzzi. A solo recording for ECM ([i]Kultrum[i], 1983) marked the beginning of an international career. Besides his work as a leader — recording in various formats, ranging from solo outings to discs with the Dino Saluzzi Group, featuring members of his family — he has collaborated with a disparate group of artists including Italian trumpeter Enrico Rava, guitarist Al Di Meola, singer-songwriter Rickie Lee Jones, and Polish trumpeter Tomasz Stanko.

[i]El viaje[i], the trip, had brought Saluzzi’s bandoneón all the way from Campo Santo to Germany. “I not only took the bandoneón back home, I took my grandfather too,” says Saluzzi, who now lives part of the year in Buenos Aires and part in Munich. Recently he closed another circle, bringing his career back to his small hometown.

On March 17, Saluzzi hosted and performed at a celebration in Campo Santo, held next to his old house. The event kicked off a renovation project that will transform a 1770 slaughterhouse into a cultural center featuring a performance space and classrooms for related activities. Not only does Salta have a rich musical tradition, but geographically and historically, it’s also part of the Andean culture stretching from northern Argentina deep into Bolivia and Peru. Salta can be “another New Orleans, a meeting point of cultures,” Saluzzi says.

In Saluzzi’s life, Campo Santo, Salta, always feels far away, and always nearby. “People ask, ‘Where does your music come from?’ And I tell them about leaving Campo Santo, about going back and not finding what once was, about [i]always[i] leaving,” he says. “[i]That’s[i] where the music comes from.”

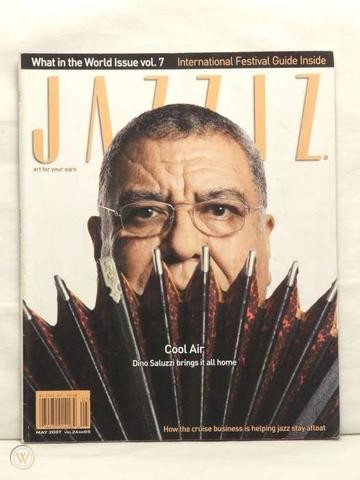

This feature was the cover story for the May 2007 issue of JAZZIZ Magazine